The Bookshop of the Broken-Hearted

Robert Hillman (Text Publishing, 2018)

‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,’ wrote Theodor Adorno.

For a whole generation after World War Two, few novels were written about the Holocaust. It seemed too soon. Only in the nineteen-eighties did writers feel more confident that they could write about it without throwing the typewriter across the room with a cry of horror and despair. Sophie’s Choice by William Styron and Thomas Keneally Schindler’s Ark (both published in 1982) showed it was possible to write about the fate of the Jewish people under the Nazi regime with sensitivity as well as a clear artistic purpose. Since then, the Holocaust has become a frequent background for both fiction and movies, including the highly-praised Book Thief by Markus Zusak, another Australian like Keneally. For any writer, the dangers of writing about that period are legion; how easy to stray into treating what happened with mere sentimentality, a lack of the right kind of respect, or – almost worse – to bring that cruelty and horror into the domain of the normal through familiarity.

Robert Hillman ventures into this perilous territory with a new novel, The Bookshop of the Broken-Hearted. The year is 1968. A farmer, Tom Hope, has lost his wife, Trudy, not once, but twice. She runs away first to be with another man, and then again to join a religious cult. To add injury to injury, she abandons a child with him for a few years – long enough for the farmer and the boy to bond and love each other – and then takes him away again. Bemused and alone again, Tom considers himself a hopeless husband, a hopeless man. At this point, a newcomer opens a bookshop in the local town: Hannah Babel, an immigrant from Hungary. The plot is sprung.

Tom Hope is a simple man. A dab hand with farm equipment, metalwork, or a sick sheep, he is ‘soft,’ reluctant even to shoot a wild dog that is killing his sheep. He has few words, seems ignorant of the wider world, is passive, dull even – just the sort of man a wife would leave, you imagine. Hannah appears a familiar literary character at first. An attractive ‘continental’ (read, ‘Jewish’) woman arriving in a conservative country town: sophisticated, educated, well-dressed, and setting the feathers flying among the men.

The town is full of memorable characters, from the randy butcher to the eternal spinster. There is a flood. There is a wedding. There is a murder. More than one, in fact . . . around six million in total, including Hannah’s first husband and little boy who are killed in Auschwitz. Here, then, is the challenge Hillman sets his characters: how can you bear to live, let alone love, after such tragedy, such loss? How can you have hope? Into this maze, Robert Hillman leads his characters in The Bookshop of the Broken-Hearted.

Hillman is a practised and masterful storyteller. The plot is ‘frictionless,’ carrying the reader forward eagerly as the pages are turned. Description of people and places is spare; the narrative pauses only occasionally with a telling detail. This is most obvious with ‘Hometown’. ‘You can’t have a wedding without sausage rolls,’ Hannah is firmly told by Bev from the CWA. Anyone who has lived in the country will recognise Hillman’s affectionate, sharply-drawn evocation of the suffocating yet also comforting familiarity of small town life. Once Tom and Hannah become lovers and marry, they begin to change. The reader’s initial impressions of them are forced to change too.

In Hannah’s presence, Tom is forced to grow up. His relationship with his first wife, Trudy, was in monochrome, either adoration or bleak despair. With Hannah, he learns about love as coming to understand that someone else actually exists in the same way he does, and the extraordinary struggle to accommodate sharing one’s existence with another person. This is profoundly true as he discovers Hannah’s past; she even has to educate him about the existence of the death camps and who the SS were. He learns the tenderness with which to manage her feelings, while at the same time, preserving his own integrity as a person. This becomes a crisis when his little step-son, Peter, runs away from his mother to be with Tom. The thought of having a little boy in the house and developing affection for him is unbearable to Hanna, whose own son was taken from her at Auschwitz to be murdered. She feels there is no choice but to flee.

Hannah, too, changes in Tom’s presence. We learn more about her experiences in the 1940s. It is as though the reader sees a pencil sketch turn to an oil painting with colour and subtle depths. Her initial exotic ‘cosmopolitan’ persona is revealed as a protective outer layer to her character, as she lowers her defences with Tom. He (and the reader) begin to see her complexity and pain and courage to somehow carry on living with the burden of horror she has known.

Among other things, The Bookshop of the Broken-Hearted is a portrait of a good marriage. Being together challenges Hannah and Tom to mature and to become better people. They learn when to compromise and when to not. They learn when to be together and how to be happily apart. Tom can never completely know Hannah’s pain, but he knows its shape and how to respect its presence. In Rilke’s telling phrase, ‘Love consists in this, that two solitudes protect and touch and greet each other.’

In Robert Hillman’s impressive canon, The Bookshop of the Broken-Hearted is possibly the best book he has ever written.

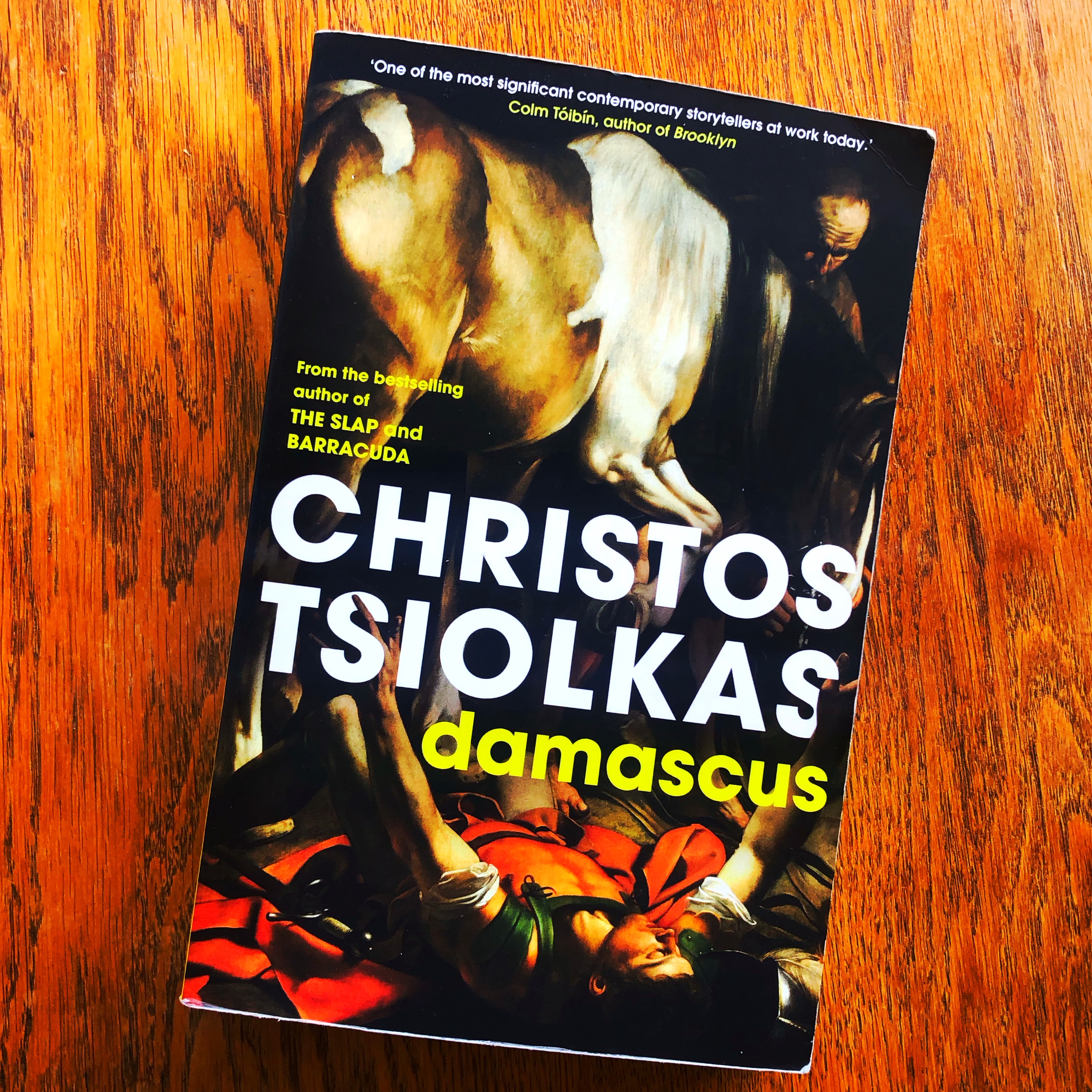

Image: Text Publishing

Great article Paul. You mentioned sentimentality/respect. Isn’t using this title a case of trivialising? If it refers to what happened in the war?

Thanks . . . I guess I felt ok about the title, as the novel is about hope and love in general, not just relating to Hannah’s experiences. And the song isn’t trivial, more like a hymn if you recall the words. https://genius.com/Jimmy-ruffin-what-becomes-of-the-brokenhearted-lyrics