The best advice I’ve heard about writing? ‘Don’t’.

Imagine all the wonderful things you could do instead with those countless hours for years to come. You could learn to speak passable Italian, join a gym and develop perfect abs (whatever an ‘ab’ is), practise an instrument until you become an seriously good saxophonist or cello player . . .

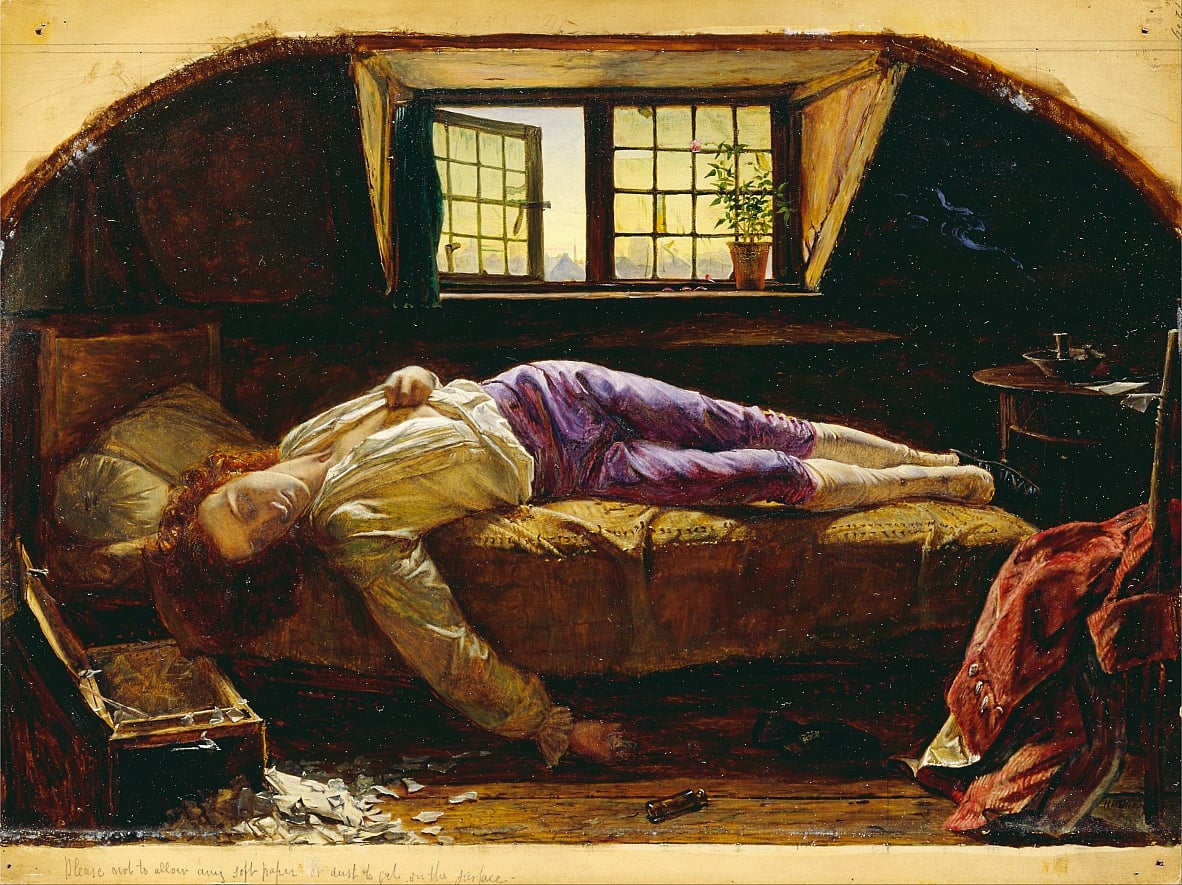

For some reason, though, there are people who would rather spend that time writing. They actually choose to spend every possible hour alone in a room making up an imaginary world. Despite it being their heart’s desire, though, actually putting words on a page is torture. They will do anything to avoid making a start – doing the washing, tidying cupboards, checking their phones, or doing ‘research’. When they make the plunge and actually start writing, it’s a process that takes years without knowing whether a single other person will ever read it. Martin Amis once wondered if people realised that an author’s life consists principally of staring through a window, scratching one’s arse, and drinking lukewarm coffee. And all this effort with no guarantee that an agent might be interested, that a publisher will actually read (or even notice) your manuscript, or that it will ever be published or read. The possibility of all these is remote. If your manuscript is actually accepted, then there’s the inevitable rewriting, the editing, the proofing. All this can take yet another year or more before publication. Why do we do it? Wouldn’t you rather learn to speak Italian?

I sometimes envy painters. They can work towards an exhibition, have no pesky editors pointing out errors or suggesting improvements, and can be confident of putting on a public show every year or so and make respectable sales. For a writer, there is also an expectation that you will do a lot of your own promotion, speaking publicly and pumping out social media posts. Many authors are shy, introverted types who struggle with this additional role. But there is, of course, the thrill of opening a box to see the first copy of your book. There is a launch and reviews . . . then a week goes by and thousands more titles have been published, then another week. Around half a million books are published in English every year.

One of the most sobering experiences for a writer is entering a second-hand bookshop. Here they are . . . row after row of yesterday’s best (and not-so-best) sellers. Every single one of these dog-eared paperbacks was once brand-new, excitedly hugged to the author’s chest, launched with a clink of champagne glasses, and intently discussed at book clubs. Out of the dusty silence of the bookshop comes a whisper, ‘You too will end up here’.

It’s no wonder many writers are tempted to focus on short-form writing for Medium, Substack, and similar platforms. There’s the gratification of instant publication and a more immediate response from readers. It’s a snack not a meal, though. Writing a long-form work like a novel is a vocation. And as with any vocation, there are occasional ecstacies as well as the agony, and this makes it worthwhile. For some people – writers as well as readers – a novel is an escape into an alternative world for a while, a place that makes comforting sense. There’s the satisfying arc of a story topped by a neat conclusion – unlike the jumble of IRL. Other works, though, turn their face to confront real life: the horror of time passing and the fact that – try as we may to ignore it – life has no higher meaning or purpose. These are big questions but they are ingrained in every moment of our lives and in our deepest worries.

‘The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers’.

James Baldwin wrote, ‘The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers’. Writing, as well as reading, a good novel, then, allows us to enter another world which helps us to see our lives anew, to question assumptions and received ideas. All this effort by the writer, then . . . only for the book to end up a few years later in a second-hand bookshop in a country town with a copy of a Dan Brown book in the window surrounded by dead flies. And then the door jangles and someone walk in. They take your book from a shelf. An hour later, they are curled in a chair reading it with a mug of tea to hand. Everything was worth it.

Image: Henry Wallis. The Death of Chatterton (1856)