I remember exactly the day I decided not to grow up.

I was twelve years and 364 days old. The following morning I would wake to birthday cards in the mail. There would be presents to unwrap at a party in the afternoon. This year though, anticipation was mixed with dread. There would be 13 candles on the cake. From tomorrow I would be a teenager, and after that you became a grown-up.

I liked being a child. I especially enjoyed staring out of the window, watching clouds change shape. A ship slowly turned into a piano, and then a cliff face hanging in the air. But I had seen what happened to other boys when they became teenagers. It wasn’t an attractive prospect. Their faces erupted with spots. They got boils on their necks. Limbs started to grow at unequal speeds. Stray hairs sprouted from their chins. They had to spend months – years even – preparing for exams and probably missing Star Trek on TV.

From my observation the world of grown-ups, too, was agonisingly boring. A conspiracy of tedium. My parents had to work every day whether they felt like it or not. They had to wear the same dull clothes every day; as a nurse, my mother even had to wear a uniform. They had to do the washing and ironing and pay the bills and keep the garden tidy. They worried about money all the time. There were whispered conversations about the cost of school uniforms. Being grown-up was a strange totalitarian state to which I seemed destined to be exiled in a few years. The scale and complexity of this world awed me: I felt like a figure in a Jeffrey Smart painting, small and fragile, overshadowed by vast industrial structures. My entire spirit revolted at the thought, that evening before my thirteenth birthday.

Everything happened exactly as I feared. The following year, my voice broke. My schoolboy complexion erupted into a volcanic landscape of red pustules. Hairs spiralled zanily out from my chin. When I shaved, the razor lopped the heads off my spots so that they bled. I went to school with little squares of tissue paper dotting my face, feeling like an outcast from a leper colony. My only consolation was the sight of other boys with just as many spots dotting their faces. It baffled me that one of the worst-afflicted seemed unconcerned by his appearance, no more than his beautiful long-legged girlfriend, captain of the netball team. There was more homework too, of course, but that at least I didn’t mind.

Finally, after all the study and when there were no more exams for me to take, I discovered that I had become a grown-up. I wore a suit every day. I sat in meetings discussing budgets and timelines and contract deliverables. I discovered the benefits of adulthood too: those things I knew little about on the eve of my thirteenth birthday. There was sex of course. There was travel. There was work: the joy of doing something well. And then there was love.

A few decades on, I have lived in five cities, thinking each was my home. I have had four professions, each time becoming restless and abandoning it for another. And I have discovered something else. That twelve year-old boy never did grow up after all. He is still there, gazing dreamily out of the window, chin on his hand, happily watching my life unfold and repeatedly re-make itself, as he once watched a cloud change shape over and over again.

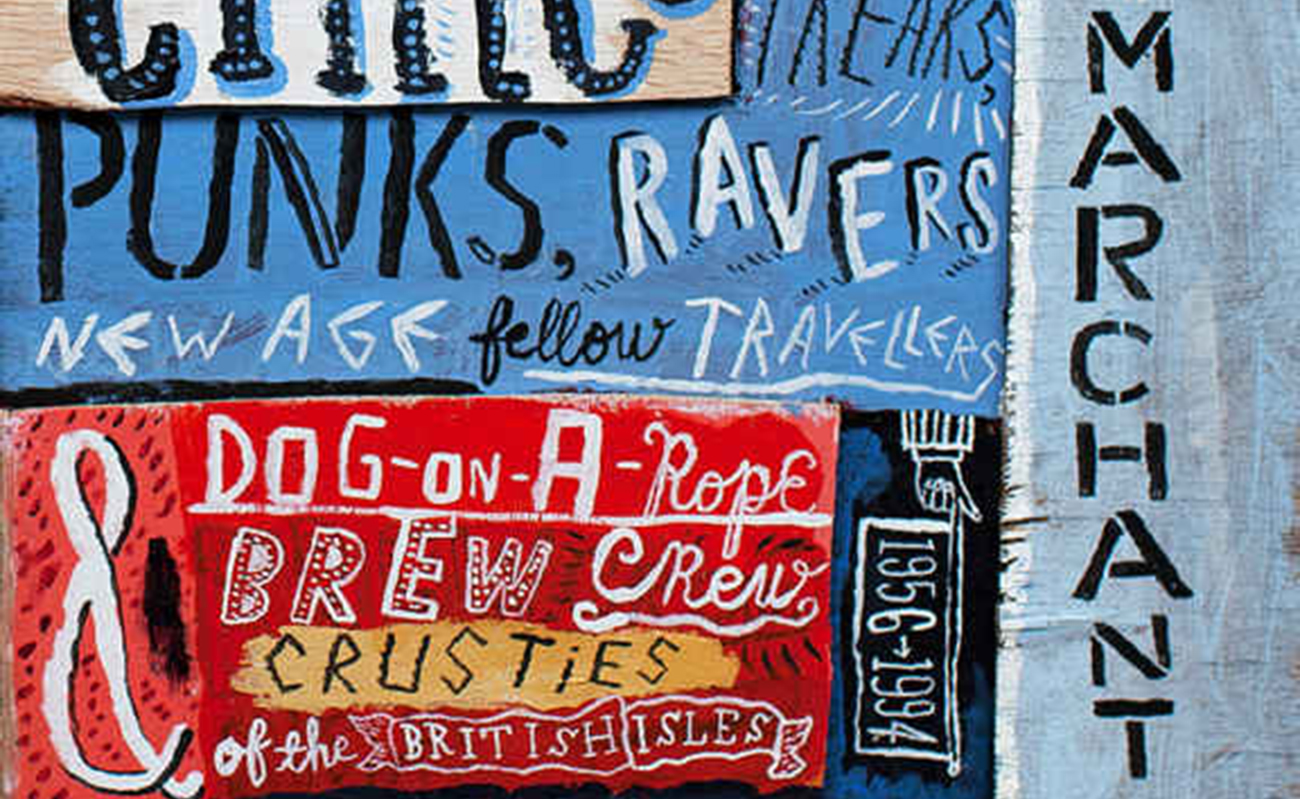

I discovered as well that there were other people who had never grown up. I know them by certain signs. And if we ever meet, you and I, perhaps we too will know each other and exchange a smile of recognition.