THE MAN WHO LOVED CHILDREN

Christina Stead (1940)

When was the last time you hated someone? I mean really hated someone, so much so that you would happily see them die? A person who bullied you at school perhaps? Someone who has hurt a child or an animal?

It doesn’t do, of course (or at least to admit it), but within a few pages of starting Christina Stead’s 1940 novel, The Man who loved Children, I felt in myself an unexpected and visceral hatred of both the ‘Man’ and his wife, Sam and Henny Pollitt. Exploring this reaction took me till the end of the book.

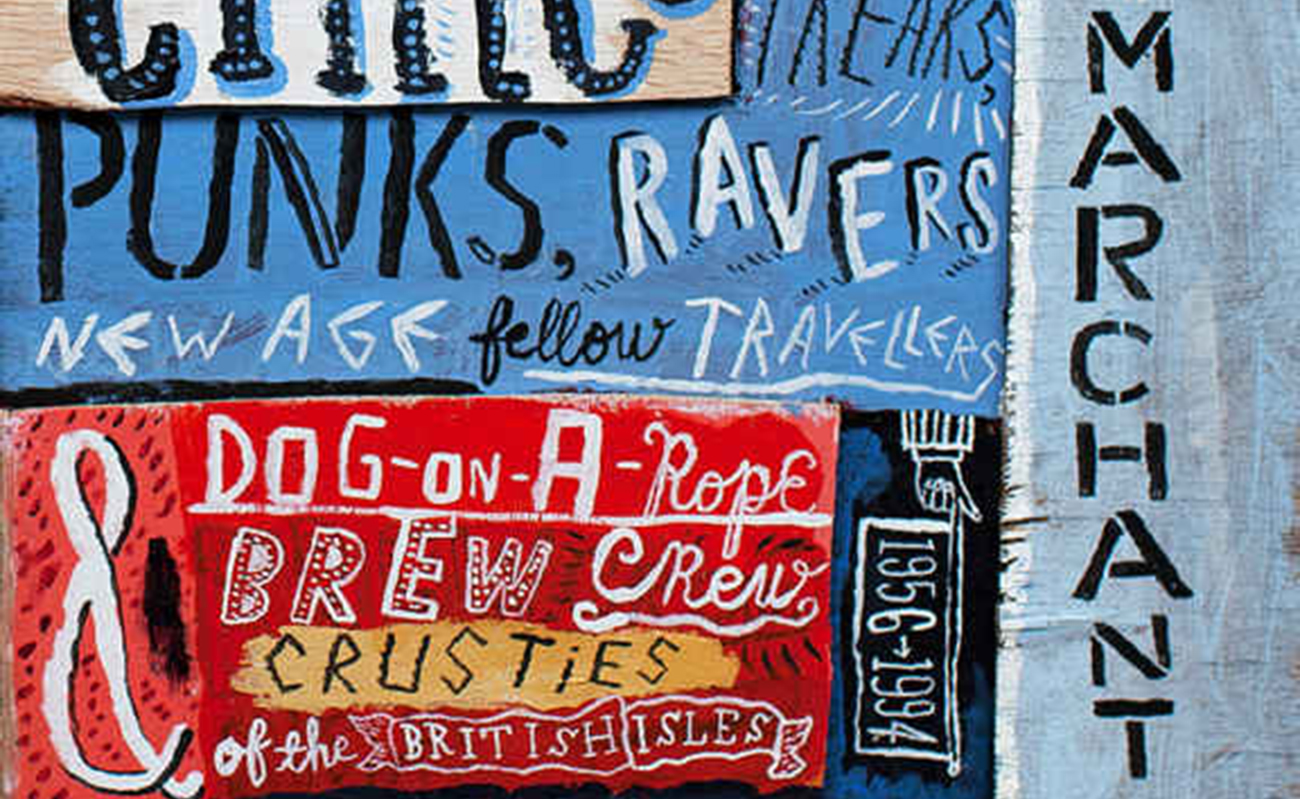

The novel is a classic of Australian literature, familiar from its 1966 re-issue with a dust-jacket featuring Russell Drysdale’s Two Children, one of his eerie outback paintings from the 1940s. Unlike the cover image, though, the novel itself is set in the suburbs of Washington DC during the 1930s. Stead had fled Sydney in 1928 and spent much of the remainder of her life in the United States. The origins of the story are avowedly autobiographical, based on Stead’s memories of her overbearing father, a renowned biologist and conservationist (Mount Stead in the Blue Mountains is named after him). What she does with this personal material is extraordinary however.

The Man who loved Children is one of those books you feel you should have read. It’s sat on my bookshelf (or rather the waist-high pallisade of books that lines my bedroom walls) for a good ten years, and last month I decided to tackle it at last. Except that a dutiful ‘tackle’ was not what I found. Stead’s prose thunders and crackles with all the energy and excitement of a storm. How often can you say that a book is truly exhilarating to read?

The story opens with a description of the Pollitt household. In a big ramshackle house live five (or is it six?) children, the eldest being Louie, Sam’s daughter with her first wife (now deceased). When Henny returns home from town, the children crowd around to see what she has bought; she dismisses them with lines that may equally be good- or bad-humoured – ‘What do you mean sneaking up on me like that, are you spying on me like your father?’ – then retreats to her room with a cup of tea.

As Henny sat before her teacup and the steam rose from it and the treacherous foam gathered, uncontrollable around its edge, the thousand storms of her life would rise up before her, thinner illusions on the steam. She did not laugh at the words ‘a storm in a teacup’. Some raucous, cruel words about five cents misspent were as serious in a woman’s life as a debate on war appropriations in Congress; all the civil wars of ten years roared into their smoky words when they shrieked, maddened at each other; all the snakes of hate hissed.

When Sam returns from work each day, there are cheers and picnics and building of tree-houses and speeches about democracy and freedom and the future of mankind . . . but it is Sam who is always in charge; Sam who does the talking and won’t brook contrary opinions; Sam who keeps Louie cleaning and cooking, as the eldest girl in the house.

When the children are in bed, they hear fearsome, screaming arguments between their parents that go on for hours. For weeks on end, Henny does not speak to her husband, but leaves notes for him or uses one of the children as an emissary. These communications are often about money. The spoilt child of a spendthrift father, she keeps secret from Sam that she is always hopelessly in debt. He would earn a reasonable salary as a government scientist, but Henny has no interest or capacity for doing anything with money apart from spending without thought. Debt is easy; you do not have to make any special effort to make it happen. It simply comes about when you do not budget, as Henny discovers. The more she owes, the more terrified she is of Sam finding out. In the end, she is shamelessly borrowing money from anyone she can: family and tradespeople, her children’s teacher, and she even sells her body for favours to a man she despises (and who fathers the youngest of her children). One by one, she disposes of everything of value in the house, and even steals from her son’s savings tin.

It is not the Pollitt’s treatment of each other alone which is fascinatingly repellant; it is how they treat their children. The sensitive Louie, on the verge of adolescence, is beaten by her father when she is recalcitrant. More painful to her, though, is the humiliation she suffers. Henny regularly reminds her step-daughter of how unattractive she is, how clumsy and overweight. Sam openly mocks Louie’s love of literature (her only refuge from family life). He even takes her personal notebook and reads it aloud to the others in a mocking voice.

Jonathan Franzen notes this cruelty in his admiring essay on the book:

Although its prose ranges from good to fabulously good — is lyrical in the true sense, every observation and description bursting with feeling, meaning, subjectivity — and although its plotting is unobtrusively masterly, the book operates at a pitch of psychological violence that makes Revolutionary Road look like Everybody Loves Raymond. And, worse yet, can never stop laughing at that violence!

The pitch of the story rises as Sam goes on a long scientific expedition in Asia, loses his position in obscure circumstances, and the family are forced to move out of their home. The Pollitt parents grow ever more hateful to each other and the reader as the stress of their home life increases. Turning the pages is like hearing an orchestra play ever louder and faster, at a higher and higher pitch. It is here that a lesser author could literally have ‘lost the plot’ but Stead stays firmly in control. How tempting to make outright villains of this self-centred pair, like a couple of Dickensian grotesques. Yet this is where she turns the reader’s hatred of them (or this reader anyway) back on us. After all their repellant behaviour towards the children, Stead gives us glimpses of their inner lives, forcing us to acknowledge their three-dimensional, tragic characters, trapped in their own folly. Sam does love Louie, he makes clear, but is incapable of understanding or engaging with her in any way. His idealism about humanity is sincere but abstract. Henny is an appalling, selfish creature, and yet one can sense the maddeningly powerless frustration of being married to ‘the great I am’ as she calls Sam, who has Old Testament attitudes towards women, despite all his claims of modernism.

Louie is the main victim of their errant parenting. Her increasing pain at their humiliation of her reaches a crescendo when she begs to leave home, and Sam tells her she will never leave but stay always to look after him. In a scene which is ghastly and quite believable at the same time, she decides the only solution is to murder her parents. In a dreamlike state she mixes poison into their tea, hesitates, but sees Henny drink and fall dead before she can stop her.

It’s all too easy for everyone to believe the hysterical Henny took her own life. Sam insists again that Louie stay to look after him and the other children, but now she feels free and walks out of the house, never to return. The end of the novel is the beginning of Louie’s life.

The Man who loved Children is a masterpiece, and Christina Stead is rightly (if insufficiently) recognised as one of the greatest Australian writers of the twentieth century alongside Patrick White. Her 1946 novel, Letty Fox, was banned in Australia for over ten years due to its ‘salacious’ centent. I can’t wait to read it.

Image: Russell Drysdale, Country Child.