Here’s a handy tip for the festive season. If you fall ill at Christmas – and I’m talking about collapsed on the floor, in pain, with blood everywhere, the works – then try not to do as I did a few years ago: stay in a remote cottage without mobile coverage and far from the nearest road.

Despite spasms of pain, I felt strangely calm. There was absolutely nothing I could do to make a difference. Everything was out of my hands. It was up to others now, especially my wife speeding to the coast where there was a mobile signal to call triple-zero. At last I saw her car returning across the paddock toward the house; behind it, a bulky ambulance bobbed up and down across the rough ground.

The ambulance crew took charge of the scene like angels in bright, reflective clothing. My wound was dressed. Question after question was gently but persistently asked. How wonderful it felt to be lifted up, carried into the ambulance and driven away! How good that first injection felt to take away the pain! How pleased I felt with my presence of mind, hugging a plastic bag with book, phone, and charger safely inside!

It took almost an hour to reach the nearest hospital, spread out on the hillside over a seaside town. The ambulance doors opened, unfolding a view of paperbark trees, rooftops, and a harbour far below with fishing boats bobbing at anchor. The view disappeared as I was swiftly wheeled into the emergency department. My curious calmness had not gone away. How interesting it was to be taken away on an adventure with my new friends in their hi-vis uniforms – what would happen next?

I lay alone in a room for a few minutes before two young women walked in wearing t-shirts with Happy Birthday Jesus! in sparkly letters on the front. More questions. Blood pressure check. A blood sample taken. Cannula inserted onto the back of my hand (interesting, I thought, examining the device.)

A bearded man entered, in a white coat and a stethoscope around his neck, those universal symbols. After a murmured conversation with the nurses, he came forward.

‘Hi, I’m Brendan. Sorry about the fucking Christians,’ he said, gesturing towards the nurses’ t-shirts. ‘There’s a lot of it about this time of year . . ’

One of the nurses stuck her tongue out at him then grinned. They obviously knew each other well.

‘We’ll keep you under observation for a few days,’ said the doctor after examining me. ‘If you’re lucky, it’ll heal by itself. If not, the surgeon will take a look and probably want to operate. You’ll need to recuperate after that, so you’ll miss Santa calling, I’m afraid.’

‘But look on the bright side,’ said one of the nurses. ‘You’ll be here for our carol service on Sunday.’

Now it was the doctor’s turn to roll his eyes.

I was with Brendan. Christmas in Australian meant nothing to me, after a childhood in northern Europe. As a nine-year-old in Wales, it had been easy to imagine Good King Wencelas and his page trudging through the snow on the hill right behind our house. So how could it be Christmas in mid-summer? Reindeer and snowflake decorations hung listlessly from lamp-posts in town, looking cheap and tawdry in the bright sunlight. If we were staying near the coast, there would be swimming in the afternoon, then dinner cooked on a barbecue. But Christmas? It just didn’t feel right. The magic wasn’t there.

A real Christmas, I knew well, took place in dark and bitterly cold weather. My bedroom window was crazed with frost patterns when I woke to find a pillow case full of presents at the foot of my bed. A coal fire burned high as we gathered around the table to eat a turkey lunch. Afterwards, there might be time for a walk before darkness fell by four-o-clock in the afternoon. In the evening, we sat around the fire, watching television, passing around a Terry’s Chocolate Orange in its golden wrapper. When we tired of chocolate, there was a box of dates (never eaten at any other time), the lid bearing an old-fashioned illustration of two camels strolling nonchanantly past a pyramid.

On Christmas Eve, I had gone out carol singing with the choir from the local church. Wrapped in coats and balaclavas and sheepskin gloves, we walked through the snow to every house in the village. We took turns to carry a wooden pole with a candle glowing inside a lantern. At some houses, we were ushered inside (‘Don’t worry about your shoes’) to the bright fireside where mugs of hot chocolate and mince pies were passed around and we sang another verse of ‘Silent Night, Holy Night’.

I had a secret disdain for Christmas in Australia, therefore, and no interest in staying in hospital to endure the carol service. But as Doctor Brendan had warned me, the surgeon decided I needed an operation the very next day. When the following Sunday came around, then, I found myself being pushed in a wheelchair into the hospital forecourt.

The place was crowded. It looked like half the town was there. The Hospital Carol Service was obviously a big deal in the social calendar. Over by the car park, a pair of barbecues was being fired up, sending a smoky hint of sausages into the air. A fisherman in waders had just arrived, a bucket of prawns in each hand. I spotted members of the Rural Fire Service, too, directing traffic and showing people where to go. Filling the forecourt were local families and holidaymakers from nearby campsites, some in saris or turbans, with their children at the front so they could see. Some were dressed in costumes they had unwrapped as presents that morning. The whole scene was like a Qantas ad. Then there were hospital staff, patients like myself, and in the centre, a choir of nurses. There must have been a dozen of them, all wearing sparkly Happy birthday Jesus! t-shirts. Elaborate, home-made tiaras rose from their heads, with lights flashing on and off. It was an extraordinary sight. I spotted Brendan nearby and raised my eyebrows, but he just grinned back.

An electric keyboard played the opening notes of ‘Once in Royal David’s City.’ The crowd began to sing, raggedly at first, then picking up confidence with every verse. The familiar canon of carols followed, all those tender songs I had once known by heart as I made my way through the snow in faraway Wales, carrying a lantern on a pole from house to house. You couldn’t have imagined a more different scene. My eyes were drawn more and more, though, to the children at the front of the crowd, with here and there an eight-year-old Wonder Woman, cowboy, or Princess Leia. All were staring at the Christmas nurses, moved to silence by their glittering lights and costumes and the strength and harmony of their singing.

Wasn’t this the magical excitement I had once felt and now lost for so many years? When you are a child, so much is new and for the first time, and full of a wonder that cannot be repeated. Maybe Christmas for them in Australia was the same as it had been for me at home, after all. The heartfelt letter to Santa Claus. Counting down the days. A special trip into town to see the department store window display. Standing quietly in front of the nativity scene, seeing the stable, the kind-faced cow watching on, and the noble orient kings appearing on their camels to kneel before a new-born baby whose name was love.

But I had walked away from Bethlehem a long time ago. Around the age of fifteen, like many people, I become entranced by the beauty and logic of Darwin’s writings. I was baffled at the need for religion, for a child-like explanation of the entire universe, mysteriously imparted to some mammals on the third planet from the sun. It was sad to realise I would never know those Christmas feelings again. I was exiled from that safe and cosy world of cardboard certainties, but it was a willing exile. There was a price to pay, though, I now understood. The beauty of Christmas, childhood, and the past can be treasured as memories, as a part of who you are, but you can never go back. You betray your existence by clinging to the past.

I was grateful to the Christmas nurses for the care they’d given me, but had no time for the comforting fairy stories they advertised. Thanks to them and to the doctors, I would be on my legs again in a few days. I would leave the hospital and, a few weeks later, be back at work. I would be an agent not a patient. I would walk alone and be strong.

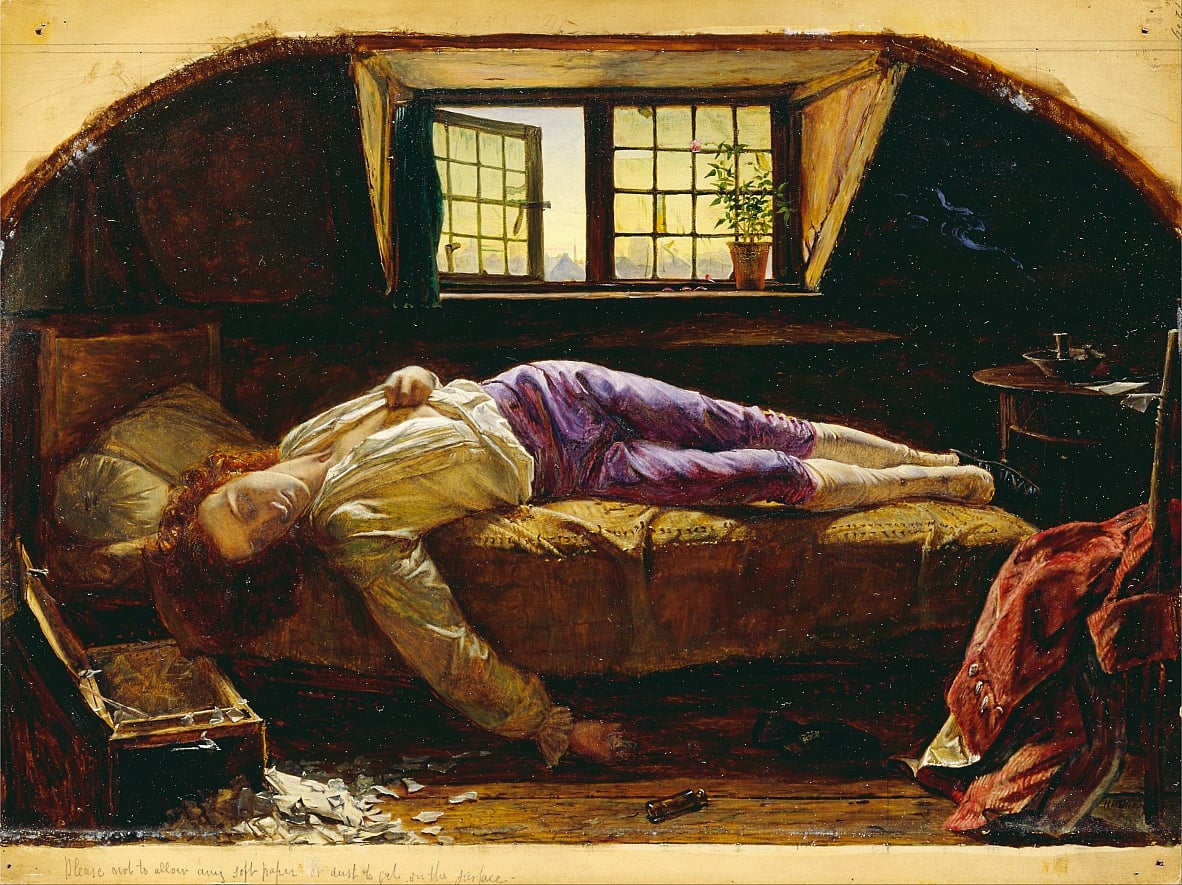

Image: Georgiono, Adoration of the Shepherds. National Gallery, Washington.

Yesterday my husband and I left Church when communion was being taken. We were standing up the front, too close really. The sermon, well written and delivered, didn’t reach me. I wanted to be there, but I felt uncomfortable actually being there. I have never left a service before the end before – that might be a fib – and it felt significant. Instead we crossed the road and walked in the park and talked about why the job of religion at Christmas is important and also impossible – although doubtless would recall our conversation (and the sermon) differently.

‘although doubtless my husband would recall our conversation differently’.

Thanks, Helen. I’m sure vicars despair at the crowds of the sentimental they only see on Christmas Eve. I went to a carol service here out of courtesy, and my only sentiment was disgust at the tin-eared version of the Bible used in readings, instead of the sublime King James.