[wpvideo XDdcoCoT]

It’s only January 2014, but already I’m confident that Spike Jonze’s Her is one of the strangest and most poignant movies I’ll see this year.

Set ‘slightly in the future’, the story is a romance between Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) and the ‘her’ of the title. She, however, is a computer interface. Voiced by Scarlett Johansson, she is like a futuristic version of Siri, exquisitely designed to respond to his needs for information, for assistance with his life, for companionship. She understands him better than anyone. Theodore takes her everywhere with him on his iPhone-like device. The relationship deepens, then takes an unexpected turn . . .

Widely-praised and Oscar-nominated in the US, the movie has provoked much hand-wringing discussion about our contemporary dependence on iPhones and similar devices. And it’s true they have changed our lives in a few short years. We have perfect knowledge, thanks to always-on Internet access in our pockets. No one needs to have long arguments about ‘who was in that Scorsese movie’ anymore. We have perfect communication, able to call or Skype anyone, anywhere, at anytime. Thanks to Siri, we can simply ask for what we want and get a polite spoken response back. It’s like having a super-smart PA who never sleeps. No wonder that people feel uncomfortable when their phone is not in easy reach.

There is an undeniable personal relationship between ourselves and our devices too, which Her cleverly explores. Think how many times a day you touch and stroke your phone, then count how often you do it with someone close to you.

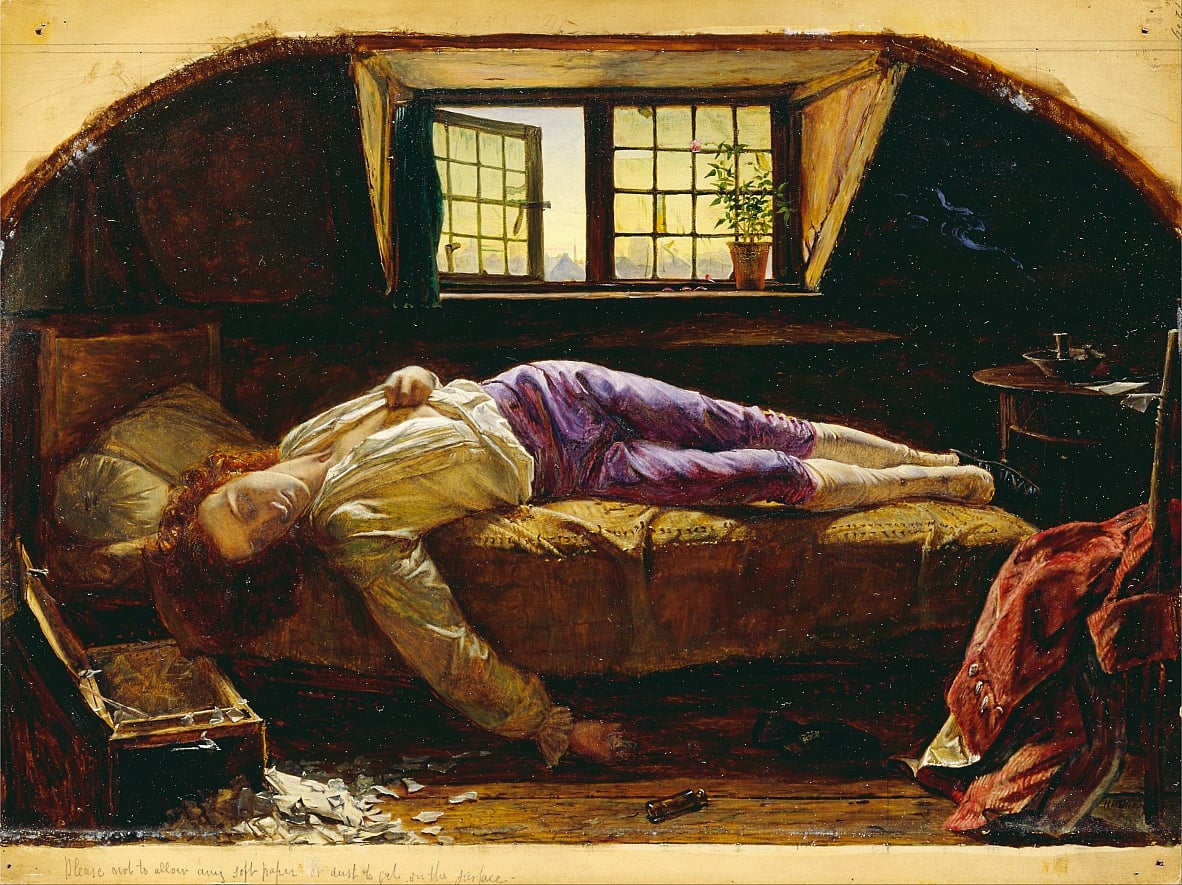

This portrayal of a relationship with an imaginary being is not new. Think of Lars and the Real Girl (2007), in which Ryan Gosling convincingly acted a man who falls in live with a blow-up doll. And there’s Pygmalion, of course, who brought his statue, Galatea, to life in the same story, told for the first time thousands of years ago. What they have in common is projection of an idealised relationship onto an object rather than a real person. I was going to write ‘inanimate object’ but with artificial intelligence, that isn’t strictly true any more. In Her, the blowup doll can talk back. In fact, it doesn’t even need a body. As research shows, conversations on the Internet are also disinhibited and can move speedily to intimacy as each person projects an ideal onto the other.

This urge for intimacy extending to objects echoes attachment theory in psychology, especially the concept of ‘transitional objects’. In other words, comfort blankets. As infants explore the world beyond their mother’s lap, most of us make some object – a blanket or teddy bear – a ‘transitional object’. This is invested with an almost magical essence of the mother, providing a portable sense of security and comfort, until the child develops confidence and can do without it.

Projecting relationships onto objects is wired into us therefore. It’s not an aberrant behaviour. When human cultures first developed, animistic and mythological beliefs gave personality and mystical powers to mountains, rocks, trees, and other elements in the world around us. These were believed to have intimate connections with our personal lives, creating a web of relationships with our environment. It was these beliefs which led to the formation of religions, of philosophy and the arts, and eventually to the evolution of modern science in the sixteenth century. The fact that they are not real is beside the point. Imagining these relationships helps us to escape the solitary confinement of our own minds, to reach out and explore our surroundings. It’s a mode of apprehension. In Her, Jonze achieves the difficult task of taking such a relationship to the extreme and exploring the consequences.

In the end, it is not treating objects as humans which causes problems, but the all too common opposite: when we treat other people as though they were merely objects.