Maigret is one the great fictional detectives, yet he is also unique, quite unlike all others. Why are stories about the Commissioner of the Police Judiciaire of Paris so different?

There’s no denying his popularity; the numbers tell the story. Agatha Christie wrote a dozen books about Miss Marple and 33 on Poirot. Georges Simenon published a whopping 75 Maigret mysteries, which have sold over 600 million copies. These aren’t potboilers either. Each is a gem of a novella at around 40,000 words. John Banville calls the Maigret books, ‘extraordinary masterpieces’ and André Gide’s praise was even higher: ‘The greatest of all, the most genuine novelist we have had in literature’. What is more extraordinary is that he wrote each book in little more than a week. For anyone who has spent agonising years writing a novel, it’s enough to make you weep. Simenon would prepare himself like an athlete – as obsessive about writing as he was about money, sex, and every aspect of his life – then shut himself away in his study, barely eating or sleeping until the job was done.

There are three principal aspects of a successful detective novel: the plot, the atmosphere, and the hero’s character. Without all three parts of this machinery working smoothly together, a book is unlikely to succeed or satisfy the reader.

The Maigret plots follow the model established by Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin and Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes: an inexplicable crime surrounded by a veritable shoal of red herrings, which by observation of details and a process of abduction, the hero solves the mystery, identifying the guilty party. However, this is probably the aspect of the story which interested Simenon least. In his Intimate Memoirs, he confessed that his writing method was to list the characters and their background, plan the house where the action takes place, and then not write a plot, but only find some incident to trigger the story, before making it up as he went along from there. The plot performs a necessary but essentially mechanical role: it provides a skeleton on which the flesh of the story can be built up.

Like other fictional detectives, Maigret operates in a distinctive setting which creates an atmosphere for the books. As 1930s LA is for Philip Marlowe, the foggy streets of Victorian London for Holmes, and the country houses of England for Poirot . . . Paris is Maigret’s manor. From the fashionable apartments of the sixteenth arrondissement to the night clubs of Montmartre, he is at home everywhere, with everyone. The city becomes a character in the novels, infusing each with a particular atmosphere, drawing in all our associations from memory, music, and movies.

It is the character of Police Commissioner Jules Maigret which differs so much from the familiar tropes of the genre. Sherlock Holmes or Philip Marlowe, Poirot, Rebus, Wallander or Vera . . . they share common characteristics. Most are loners, solitary figures often operating as private investigators. Maigret, however, is a career police officer who works with a loyal team of detectives. They live alone, often in a run-down or eccentric apartment. Maigret, however, shares a comfortable bourgeois home with his wife, Louise. They generally have something dark and unresolved in their past which haunts them (broken relationships, grief, wartime trauma). Maigret seems fundamentally happy, free of guilt or worry. They often drink excessively or take drugs (starting with Sherlock Holmes and his infamous coke habit.) Maigret likes a drink, but probably no more than the average Parisian. They have an obsessive personality, making relationships with others difficult. Maigret has none of this friction, is happily married, and enjoys nothing more than a quiet dinner with Louise before an evening walk holding hands. Finally, there’s often a signature habit (a verbal tic such as Poirot’s ‘little grey cells’, or Rebus’ regrettable for fondness British ’80s rock music, for example). Here, at least, Maigret conforms to type with the immovable pipe in his mouth as an aid to cogitation.

Maigret’s unique character and approach to criminals are the source of his charm and fascination for readers, rather than the plots or crimes themselves. Simenon described this attitude in Maigret in Society: ‘He did not take himself for a superman, did not consider himself infallible. On the contrary, it was with a certain humility that he began his investigations, including the simplest of them. He mistrusted evidence, hasty judgements. Patiently, he strove to understand, aware that the most apparent motives are not always the deepest ones.’

The Maigret novels are not so much who-dunnit or how-dunnit, but rather why-dunnit. The Commissioner certainly uses evidence, but the most compelling proof for him is that of the motivations and emotional lives of his suspects. His motto is ‘understand and do not judge’. All people are the same to Maigret. He is comfortable with anyone – whether duchess, surgeon, prostitute, or dock worker – and treats them equally and empathetically as interesting subjects who will help him to understand humanity better. His perspective is closer to that of a priest or anthropologist, rather than the hero of a traditional detective novel. The focus of Simenon’s real interest may not even be the criminal, but an informer or witness whose character is exposed by Maigret’s attention after the crime.

Detective novels are primarily for entertainment, of course, but also satisfy an unconscious need for confirmation that the world of crime, disorder, and violence can ultimately be subdued by rationality, by logic and reason. They reassure middle class readers that they and their way of life are ultimately safe. Simenon did not see things this way. For him, the chaos of humanity and its frailties is a permanent state of affairs. The best we can do is to recognise this with humility, to strive to understand it with compassion, and to ameliorate it as best we can. It is simultaneously a bleaker and yet warmer perspective on humanity.

Reviewing a TV crime series, JG Ballard mused that, behind every fictional murder, the real crime being investigated is ‘the crime of being alive. I fear that we watch, entranced, because we feel an almost holy pity for ourselves and the oblivion patiently waiting for us.’ Simenon would have nodded in agreement. What Maigret investigates is the human condition itself. There is no escaping our nature or our mortality, but Maigret is like a parent who never disappoints: the stout, dependable figure of the Commissioner is always there, pipe in hand: understanding, forgiving, and kindly as he delivers us to justice.

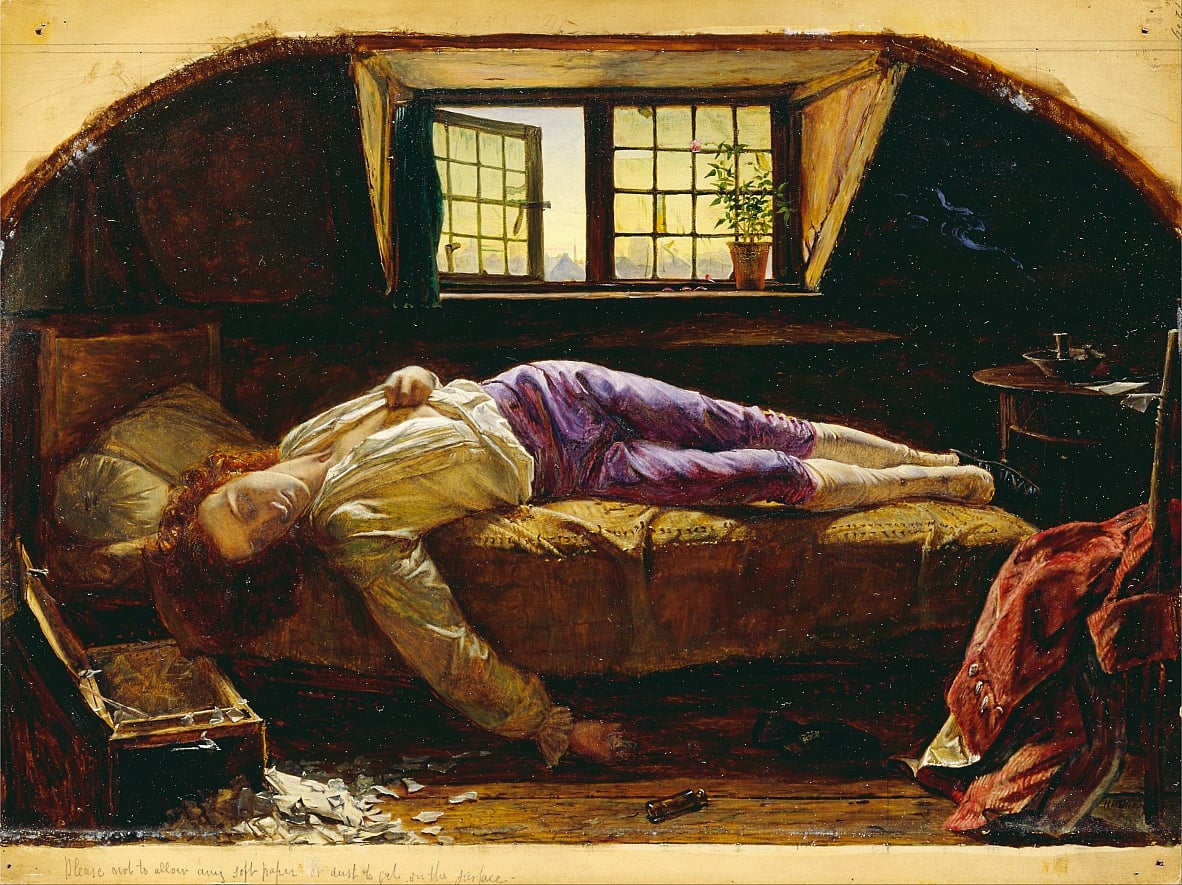

Image: Rowan Atkinson as Commissioner Maigret in the 2016 ITV series.

Brilliant essay, Paul.

Merci, M. Gerrand.

Simenon is one of my favourite writers. As you say, the Maigrets are a series of masterpieces, all character driven. Fascinating that you found the Ballard quote – he’s another writer I admire.

Holy pity indeed! Lovely writing Paul.

Merci, Hélène.

Great piece of writing that pins down the fundamentals of Simenon. I like the face he has a nice home life and has a beer or two rather than being an alcoholic or loner. He is obsessed but not to the point of destroying his marriage. The great thing about the writer is he was so prolific you never run out of books to read.