Schoolgirls aren’t what they used to be, I decided the other day.

The place was the Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne. The occasion was the opening of the Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls exhibition. Like many Australians, I thought I was familiar with the striking paintings of young girls Blackman produced between 1952 and 1955, on display in major galleries. What I hadn’t realised, though, was how very many works Blackman produced in this remarkable series. Thanks to impressive detective work by the exhibition’s curator, Kendrah Morgan and her colleagues at Heide, over 40 works have been gathered from around the world for this exhibition – mostly paintings in tempera, enamel and oil on board, but also prints, rare three-dimensional pieces, and original material from the Heide archives. The effect of seeing them all together is stunning and deeply moving.

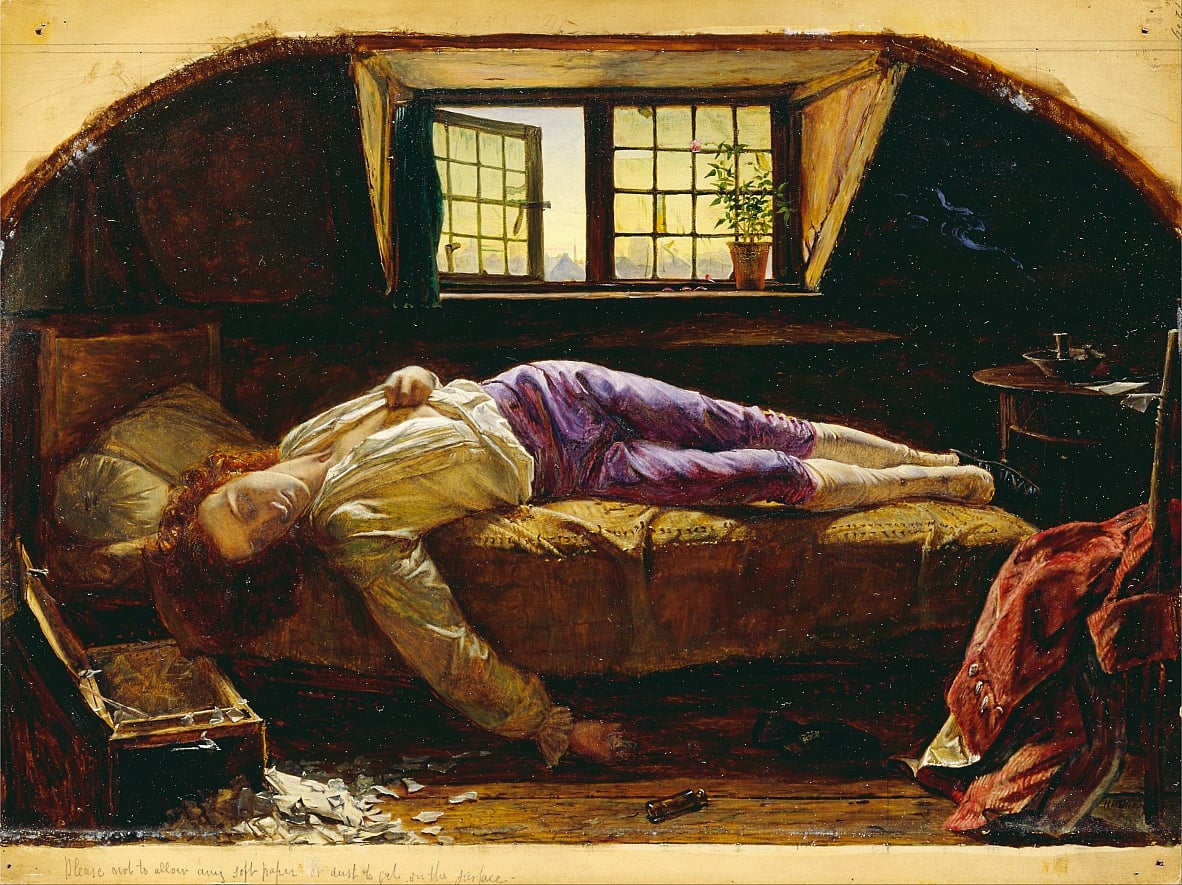

Why did Charles Blackman spend years painting these figures obsessively over and over again? And what is the meaning of these mysterious figures?

There’s been no lack of interpretation. The influence of Symbolist painter, Odilon Redon, has been noted. The notorious murder of a twelve-year old girl, found dead in an alleyway wearing her school uniform, was in the news. A friend of Barbara Blackman (the artist’s wife), had recently been killed in Brisbane. These murders would have made a deep impression on Blackman. After seeing one of the early paintings, his friend and patron, Sunday Reed, had also shown him a poem which deeply impressed him, ‘Schoolgirls Hastening,’ by John Shaw Neilson. Blackman’s artist-son, Auguste, read from this poem movingly at the opening of the exhibition at Heide.

Fear it has faded and the night:

The bells all peal the hour of nine:

The schoolgirls hastening through the light

Touch the unknowable Divine.

While these influences are undoubted, it’s important to remember the most important factor of all: the artist’s eye and what he saw around him.

Schoolgirls aren’t what they used to be in the 1950s. When I see them emerge from the local school at the end of the day, the little ones look like snails with enormous packs hanging from their back, full of textbooks, laptop computers, and hopes of becoming a web designer, a doctor, owning a business, or just making enough money to go travelling the world for a few years. The older girls loll at café tables, confidently swinging their legs as they sip on macchiatos and talk on iPhones with sparkly covers.

The schoolgirls Blackman saw had a very different life. For most, becoming a secretary or entering the typing pool was their destiny. Their Melbourne was far from the buzzing, cosmopolitan 24-hour city of today. The capital of Victoria in the 1950s was a grimy industrial centre, dominated by thousands of factories. Anything you bought in Australia at that time probably had ‘Made in Melbourne’ stamped on it. Ball-bearings and bicycles, cars and ship’s chains, lawnmowers and locks – the city was Australia’s manufacturing crucible. Factory chimneys poured out smoke from Southbank to the North and West as far as you could see. Millions of homes, too, were heated in winter by smoky coal fires.

This grim environment carried over into social life too. Almost everybody smoked all the time, at home, at work, and in public places. Public houses had to close at 6 pm, leading to the notorious ‘six o’clock swill’. In the Presbyterian suburbs of the east, it was impossible to buy alcohol at all. In this oppressive social climate, being gay was a crime and meant imprisonment. Children and women were expected to put up with unwanted touching of their bodies; it could happen anywhere. It was perfectly legal for teachers to beat and hurt young children for the most minor of reasons. When a woman became pregnant, she summarily lost her job. If you ever meet someone nostalgic for the 1950s, I’d advise keeping your distance.

Blackman was soon painting these bleak urban and industrial landscapes after he arrived in Melbourne. The images are almost devoid of people. A few distant figures lurk in the shadows, like scraps of paper which have blown there. All this changes with the first Schoolgirl paintings. The girls don’t hover shyly in the shadows but irrupt in bold, geometric shapes into the foreground of those landscapes. They play and dance. They hold hands and hug each other. They do handstands. Some cover their faces with their hands – are they weeping for some unknowable tragedy or simply playing hide-and-seek? Wherever they appear, they are full of life and dominate the previously bleak and unpeopled landscapes.

The schoolgirls are fragile and vulnerable creatures in a threatening, alien landscape. At the same time, they fizz with energy, vitality, and joy. Their existence seems to flicker forever between these extremities. Curator, Kendrah Morgan, notes that Blackman’s wife was going blind at this time, and that it’s noticeable how many of the schoolgirls have their eyes in shadow. Was the painter rendering Barbara Blackman’s situation – vulnerable yet also full of her famously indomitable spirit?

There is a deeper possibility too. Blackman was a poor young man, living in a strange new city. He has said that the paintings had ‘a lot to do with my isolation as a person and my quite paranoid fears of loneliness’ at that time. He was not so much looking at the schoolgirls, then, as identifying with them. He was unknown, unrecognised by the art world at large and hardly selling anything he produced. At the same time, he must have felt intensely aware of his own creative potency. While very personal, this tension has a universal resonance too. These paintings do not simply evoke girls playing in a dusty yard, nor the blind woman walking bravely down the street, nor even the artist sure of his talent but unrecognised by the world. The schoolgirls paintings evoke life itself flourishing in the midst of adversity – an idiosyncratic and beautiful representation of the mystery of being and non-being.

We don’t know if Blackman thought through this dilemma himself in such abstract terms, of course, let alone tried to find a solution. Instead, he articulated it brilliantly in the way he knew best. He picked up his paintbrush.

Hi Paul

Very interesting piece. Thank you. The only quibble I have is that, growing up in Melbourne’s northern suburbs in the late 40s and 50s, the air was remarkably clear and not polluted – unlike London with its atrocious smog.

We burned “briquettes” in our heater, made from compressed brown coal, but Melbourne’s geography and weather meant there was little if any concentration of smoke.

To me it wasn’t a grim environment at all. The opposite – sunny in the warmer months, chilblains and frost in winter.

Cheers

Rob

Thanks, Rob. Before my time here, but I’ve read that ‘factory fumes and smoke from household fires combined with the mist that clung to the river’s contours to create a soupy smog’. Perhaps Blackman saw the city through the lens of his depressed state, and you through the window of your sunny disposition :)

I know at least one schoolgirl who doesn’t know what a macchiatto is, and who would rather die than have spangles on her phone. Nice piece.