THE MUSEUM OF INNOCENCE

Orhan Pamuk (2008)

Once upon a time, a young peasant girl fell in love with a handsome prince . . .

She thought about him all day long and dreamed of him at night. When he rode through the village with his retinue, she felt sick with yearning. One day, she was walking by a bridge as he rode across it, his long hair flying in the wind. She saw him spit into the river as he passed by, so she ran downstream, waded into the water and caught the phlegm in her hands. She brought it to her lips. There could be no greater happiness. This was love, she thought, closing her eyes in bliss.

I was reminded of this Japanese folk story while reading The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk (Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature). Pamuk’s novel was published in translation in 2010, but only this year, early in 2017, did I reach it down from the bookcase. (I never read books when they first appear, avoiding the chatter of reviews and conversations. Reading a novel, of all things, is a solitary affair.)

Pamuk is a natural-born storyteller. The novel opens with the narrator, Kemal, describing a passionate afternoon in bed with his lover, Füsun.

In that moment, on the afternoon of Monday, May 26, 1975, at about a quarter to three, just as we felt ourselves to be beyond sin and guilt so too did the world seem to have been released from gravity and time.

Kemal was 30, the heir to an Istanbul business fortune. He would soon be engaged to Sibel, an ambassador’s daughter who, ‘according to everyone, was the perfect match.’ Füsun was a teenager, a distant, poor relation. How could anyone not read on, to discover what happens next?

Kemal happily imagines that he can keep both relationships going in parallel. Sibel is an elegant woman from the same ‘westernised’ upper class of Istanbul society as himself. Her family proudly says she has ‘studied at the Sorbonne,’ by which they mean, she has spent some time in Paris shopping, having affairs, and attending a few public lectures. Füsun is also beautiful and thoughtful, although barely 18 and the daughter of a seamstress. The closest she has been to Paris is working in the pretentious Şanzelize Boutique which sells fake european clothes.

Kemal cannot get Füsun out of his head. He allows the engagement to Sibel to fall apart, but then finds that Füsun has fled, distraught at his dishonesty. He finally tracks her down, living with her parents. He starts to visit, acting the benevolent, rich relation. Soon he is at their door regularly, tolerating their humble home as the price of being able to gaze on Füsun. Sometimes she smiles at him. The days become weeks. The weeks become months.

Kemal neglects his business. He loses touch with old friends and gives up visiting fashionable restaurants and nightclubs. In the years that follow Turkey is riven by political turmoil. There is a military takeover. Bombs and gun battles become regular occurrences. Kemal hardly notices, however, as he pursues his obsessive love. When not with Füsun, he passes the time being driven around Istanbul by his faithful chauffeur, observing moodily through the windows of the old Chevrolet how the city is changing . The ancient quarters of Istanbul are steadily being demolished and replaced by concrete apartment blocks. Kemal realises he is happiest with Füsun’s family, surrounded by the tasteless ornaments of their crowded living room, cosily watching television together.

Füsun finally relents and agrees to marry Kemal, but this decision only triggers a tragic death that seems inevitable. He still cannot let go of his obsession with her, buying the family’s house and turning it into a museum dedicated to Füsun. This shrine contains objects which remind him of her, and are infused with emotion. The actual cinema tickets from when they saw a movie together. Her shoe and a little white sock, carefully labelled and lit in a cabinet like prehistoric relics. The stub of a cigarette once held between her lips. There is even the door knob from Füsun’s childhood bedroom, sacred because she touched it so many times with her hand. This is the eponymous museum where Kemal now approaches the novelist, ‘Orhan Pamuk,’ and asks him to write his story.

The story is as seductive as Füsun, though we are never actually told what she looks like. As with the city of Istanbul, she is evoked rather than described. The novel has also been criticised for long passages where ‘nothing happens,’ for its repetition and length. These are integral to Pamuk’s hypnotic, seductive style, however. They are classic aspects of the oral storytelling mode which he draws on, circling round and round his love for Füsun until the awful conclusion. We relax and let his voice carry us forward, as though sitting with author, sipping raki on a balcony as the Bosphorus flows past.

Kemal cannot move forward with his life, yet cannot go back in time either. Like all of us, he is cursed with memory. He cannot relinquish his love of Füsun which he feels the only thing of worth in his life. (At his lowest ebb, he lies in bed, licking the door knob, which ends up in the museum, because she has touched it countless times.) The Museum of Innocence is about Turkey too, tugged between european and middle-eastern cultures. (The recent history of the country makes the novel even more poignant in this regard.) It’s about Istanbul and its inhabitants, aspiring to be modern and cosmopolitan, yet unable to let go of old ways which feel more familiar and authentic. It’s about how men and women regard each other. Most of all, the novel is about how can we live with the knowledge that each treasured moment is doomed to become the past? For Kemal, the everyday clutter of life seals his memories in amber – saving these objects becomes a way to cling on to past happiness.

Pamuk’s wry protagonist can seem at times like the last Romantic hero. He can equally be seen as a sad, pathetic fool who has wasted his life (yet what else was Goethe’s Werther?) Kemal also has much in common with Nabokov’s Humbert in Lolita – a charming, self-deprecating narrator who invites sympathy for his obsessive love. Like Humbert, Kemal’s charm distracts the reader from his actual treatment of the woman he idolises. Like Humbert with Lolita, Kemal projects his emotional obsession onto Füsun without consideration of what she actually feels or thinks or wants herself. Both women are denied any possibility of independent being by the protagonists until the very end. In Füsun’s case, she can only escape Kemal and declare independence by her own death. Through his museum, Kemal even attempts to control her after she is dead, packing it with his memories alone.

Iris Murdoch once wrote that love is the remarkable discovery that another person actually exists beside oneself. If this is love – unlike the one-sided passion of the Japanese folk tale – then Kemal remains a stranger to it until the end. This is the real tragedy at the heart of the novel.

•

In a curious twist of fiction and fact, Pahuk has bought a house in Istanbul and turned it into the Museum of Memory of the novel. In 2014, it won the European Museum of the Year Award.

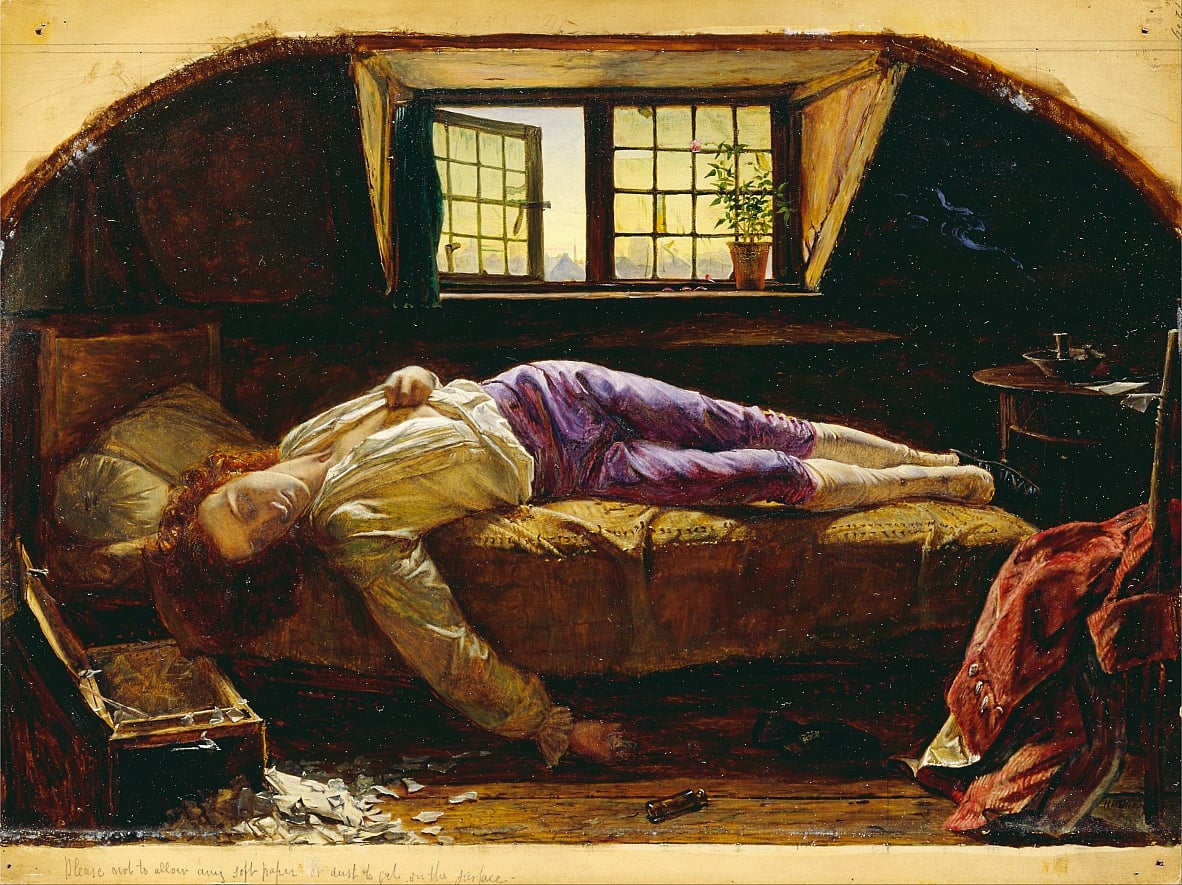

Image: Photograph of Eve Cohen