‘HOW DID THEY EVER MAKE A MOVIE OF LOLITA?’ asked the publicity for Kubrick’s 1962 movie adaptation The challenge for publishers has been can you ever illustrate the jacket of a novel about paedophilia?

I’ve been writing a review of Brian Boyd’s Stalking Nabokov recently. It took me back to when I spent two whole years relentlessly taking Lolita apart, word by word, before putting it back together in different ways. I felt like one of those guys who lovingly, obsessively takes his motorbike to pieces, lays out out all the components neatly, checks and cleans them, then reconstructs the bike again.

For all the fame (and notoriety) of the novel and film versions, one fact seems curiously misunderstood: the relative ages of Humbert Humbert and Lolita. When they meet he is only 37, not the ageing, avuncular figure he assumes to the reader. And Lolita? She is not a long-legged 17 year-old – as she appears in Adrian Lyne’s 1997 movie (above). She is not even a precocious 15 year-old whom Humbert can tell himself is ‘barely illegal’.

Lolita is twelve.

This is the most important and shocking fact in Nabokov’s novel. Lolita (‘Dolores on the dotted line’) is just a year 7 student when she meets Humbert, the stepfather who drugs, kidnaps, rapes, and repeatedly abuses her for years.

Lolita was a succès de scandale and remains one of the bestselling novel of all time (50 million copies since publication). Over half a century later, it remains a terrifying and appalling story as well as a work-of-art of genius. Despite my love for it as a novel, the emotional brutality described still turns the blood cold, and this, of course, is part of the high risk and deadly serious game Nabokov plays with his reader.

Jacket design is a crucial element in marketing fiction.

The cover is part of a book’s ‘body language’. It tells the potential purchaser what type of book to expect, hints at genre, winks to indicate the great read they’re going to have, and seduces as an attractive, desirable commodity to have around the house. The challenge for publishers of Lolita has been to fulfill these functions while respecting the sensitivity of the subject matter. Looking back over the history of the jacket designs, three very different approaches can be seen.

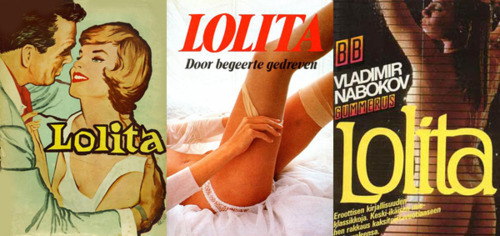

Soft porn

It is hard to believe the designers of these jackets ever read the novel. Lolita is presented as barely-clothed or naked – a frankly lubricious ‘come on’ to exploit the book’s reputation as a saucy read among readers who would not normally buy a literary novel. Perhaps these editions made a few converts, but regardless, their design ignored Lolita’s age and vulnerability – ultimately insulting the text, the subject matter, and the reader.

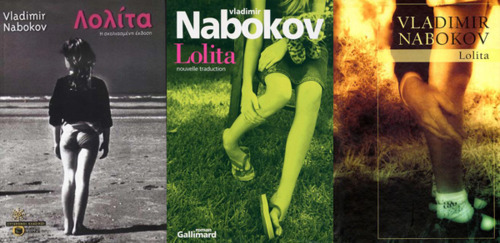

Complicity

A second group of Lolita jackets suggest her youth more accurately, but in a way that is more disturbing. The child portrayed has part of her body exposed, or shows her legs in a short skirt, being pawed by man. The crude literalism of the design also invites the reader to be complicit in viewing little Dolores Haze as a sexual object. This approach reflects the concern which critic Lionel Trilling had about the novel, when praising it on publication: ‘We find ourselves the more shocked when we realise that, in the course of reading the novel, we have come virtually to condone the violation it presents … we have been seduced into conniving in the violation.’

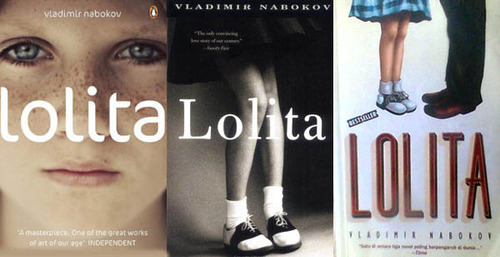

Challenging the reader

A final group of jacket designs get it right, respecting the subject matter – the abuse of a child – while challenging readers to respond to the novel as a work-of-art, recognising and negotiating Humbert’s attempt to seduce them through his prose. On these covers, Lolita’s face stares out, beautiful but clearly still a child. Her legs are shown, but they are a young girl’s knock-kneed legs, rendered as vulnerable rather than suggestive.

This is the Lolita we come to recognise in the novel: the lonely, orphaned child who weeps at night, then creeps into her abuser’s bed because, as Humbert says:

‘You see, she had absolutely nowhere else to go.’