Review of Telltale by Carmel Bird (Transit Lounge, 2022)

In 1790, French aristocrat and soldier of fortune, Xavier de Maistre, unwisely fought a duel in Turin, in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. Whether this was over a lover, a gambling debt, or some obscure eighteeenth century slight we do not know. Duelling being illegal at that time, de Maistre was sentenced to house arrest for six weeks. With only his dog and butler for company, the young Frenchman passed the time writing Voyage autour de ma Chambre, a ‘travel book’ in which he explored his room, regarding the furniture and decoration as though they were strange flora and fauna in a distant, exotic land. The book became a cult classic, light-hearted but also a testimony to how the familiar can be rendered new and strange through the imagination.

Reading

Without the support of a dog or even a butler, Carmel Bird – along with the rest of us – found herself confined to home for over a year during the COVID lockdown. Like de Maistre, she set out to make a book from this experience – drawing on the contents of her library, her memories, and her thoughts about writing. Carmel Bird has been a solid presence in Australian letters for many years – author of 11 novels, short-listed for the Miles Franklin Award three times, and winner of the Patrick White Literary Award in 2016. Bird is also widely respected as an essayist, editor, and mentor. She is especially proud of The Stolen Children: Their Stories, published in 1988. Her new work, Telltale, she says,’ is not simply an incomplete examination of the books I have read, but also an incomplete examination of myself. I suppose one can open a door upon the other. Self-examination involves, in my case anyway, an examination of my practice as a writer, bringing in many reflections on the working of the imagination, the behaviour of the unconscious mind’.

Bird begins this journey around her library with some precious volumes from her childhood, Brer Rabbit, Alice in Wonderland, Coles Funny Picture Book, and others. We are what we read, and she wonders at her different reactions to some of the stories now, perceiving the imperialist and racist assumptions which lie within them. In describing these and later favourites (Proust, Nabokov, Salinger, and WG Sebald among many others), Bird displays her love of books as objects as well as containers for words. She describes their smell and bindings, and the texture of the pages in books of different eras, noting how popular nineteenth century works are often more foxed and friable (due to the invention of wood pulp-based paper). Each book, she recognises, is a sensory experience freighted with different memories and emotions. Another realisation, as Bird voyages along her bookshelves, is how prevalent pandemics are in the background – for example, The Decameron (bubonic plague); Jane Eyre (typhus); Bleak House (smallpox), and The Secret Garden (cholera). We try not to think of them (as we are doing now with COVID) but disease and death are always with us. Bird also makes a bibliographic confession that she says her friends find ‘shocking and repellent’: when an outsize paperback is unwieldy to read (like Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature), she simply attacks the spine with an electric carving knife, slicing it into manageable sections, later tied up with a ribbon. I have no words . . .

Writing

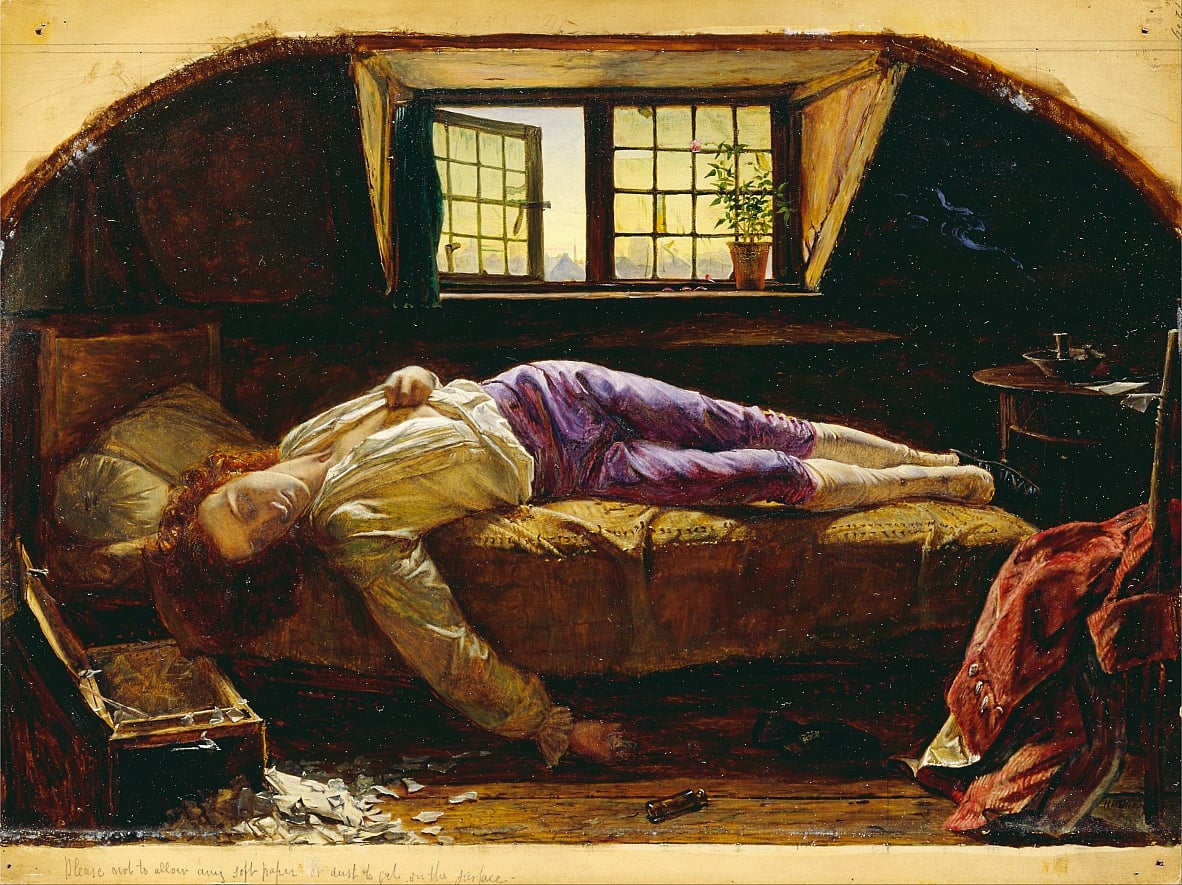

Writing about the Grimm Brothers’ folk tales, Bird confesses to fascination from an early age with horror, especially in proximity to comfort and sentiment in the tales. ‘It’s a matter of looking death in the face, really,’ she writes, ‘reading and re-reading for the music of the telling of stories of life and death. Ever after, forever and ever.’ This juxtaposition is evident in her own works, including Telltale. Along with Elizabeth Jolley in WA and Gerald Murnane in Melbourne, Bird was one of the earliest teachers of creative writing in Australia in the 1980s. Stories ‘dramatise the traces of the terrors of the human heart, and the heart picks up the traces as it registers the stories. Narrative is nerves and blood,’ she insists. Bird writes as she reads – in ‘a sort of trance’. She ponders on the necessity of solitude to writers. Quoting Robert Hughes in his memoir, Things I Didn’t Know, she notes, ‘Solitude is, beyond question, one of the world’s great gifts and an indispensable aid to creativity, no matter what level that creation may be hatched at.’ But not everyone yearns for a silent cork-lined room like Proust’s. Others can write in the midst of confusion, chaos, and worse. Some are happy to work in a busy cafe, and Bird reminds us that Behrouz Boochani laboriously tapped out his prize-winning No Friend but the Mountains on a phone while behind the wire of the infamous Manus Island detention centre.

Remembering

Telltale is not a voyage in a straight line. One thing reminds Bird of another, then another, as she veers off in different directions to recount a further memory, book, or anecdote. This feels disconcerting at first. As becomes clear, however, it is deliberate. Bird wears her tangents with pride. She acknowledges this, confessing it is a way of weaving together different periods and aspects of her life regardless of chronology: ‘Telltale is composed of two different kinds of narrative. One is warp and one is weft, and I am not sure which is really which. Will the threads hold? What patterns might I work across the surface?’ As she points out, while the physical details of a memory may be clear, ‘ the principal element that has been retained is the feeling. Perhaps the feeling is the meaning’. Memory does not possess a clock. Incidents which happened decades ago may feel as fresh as something that happened this morning. What binds this warp and weft of life is imagination – the books in her library – where, as Bird writes, ‘Strange magic is a given, and it has its own potent, mysterious logic – an ability to take a reader to the far side of time’.

Telltale opens with one of Bird’s earliest memories, of being a five year-old standing on a bridge over the Cataract Gorge in Tasmania, on the way to a family picnic. Below her was the terrifying spectacle of the thundering Tamar River. Ahead was a park with her family spreading out a tartan rug and peacocks calling to each other among the rhododendrons. She felt suspended between the past and future, between passivity and action, between one moment and the next: ‘I am so small, high up above those waters, transfixed and terrified, suddenly snapped out of everyday consciousness and into a brief flash of truth. A solitude ten thousand fathoms deep. I am alone in time and place.’ This moment has stayed with Carmel Bird all her life, gathering more and more meaning. She later discovers that this was the very day the allies fire-bombed Tokyo, killing over 100,000 civilians – the deadliest air raid in history. She wonders if a little Japanese girl there was dressed just like her in neat grey socks. In Telltale‘s final lines, she recalls being a child again back on a bridge over the abyss, full of horror and fascination. The memory is outside time. Bird still stands there, suspended, and – thanks to this moving and enchanting book – she always will be.

Oh Paul I am very moved by your review. Thank you for your supremely careful reading, and for your tender and comprehensive review.

>

Great review, Paul.