In dreams begin responsibilities WB Yeats

Two enormous faces – each the size of a house, it seemed – leaned towards each other. Slowly they kissed, lips grazing against each other in unashamed Technicolor before the two mouths opened to each other. As I realised what was happening, I was overcome with unease and felt sick at the sight before me. Something felt terribly wrong.

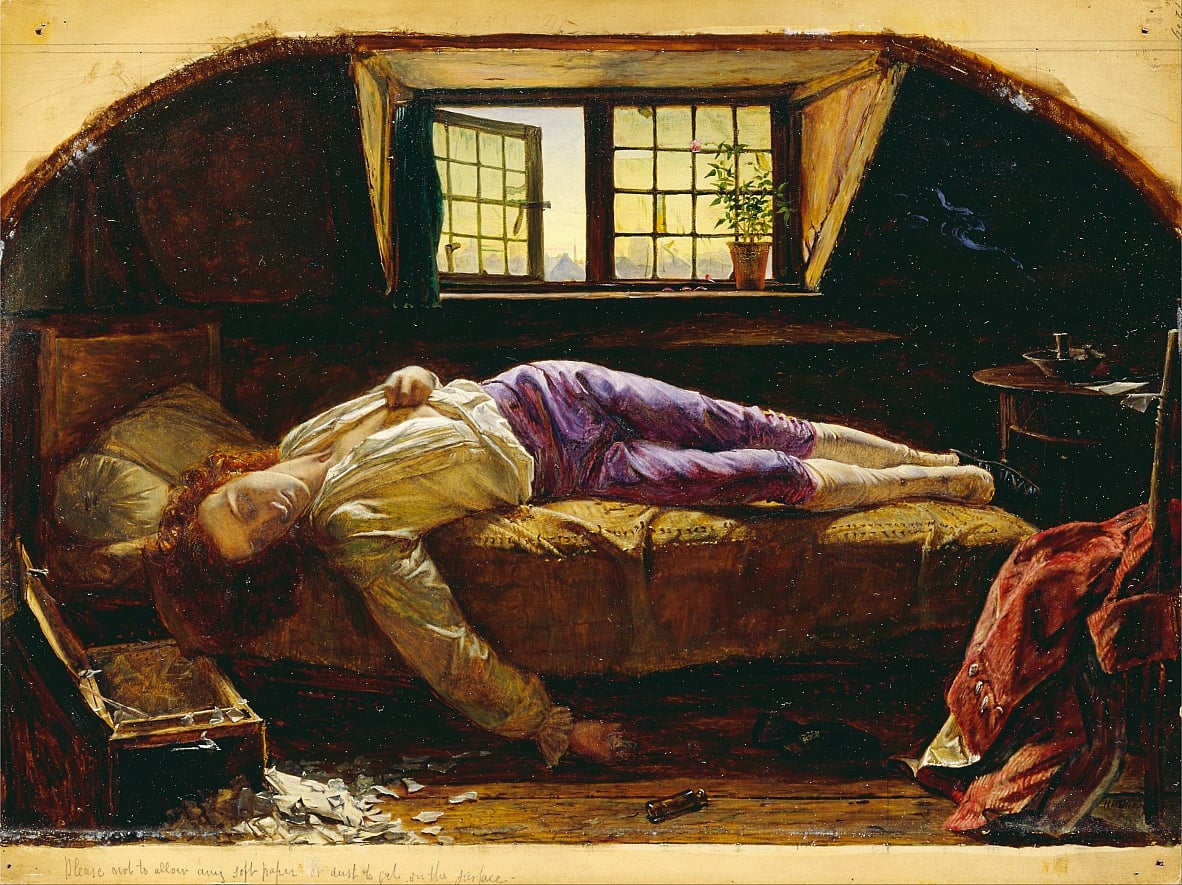

I was too young to see this movie. At the age of eight, I was already in love with films. Every Saturday morning, I took myself to the local cinema where we lived in a quiet suburb of London, My taste was Disney classics or science fiction adventures, however, not the romantic drama projected in front of me now. But why was I seeing this very adult film? I can only think that my parents had tickets for a special showing and a babysitter had let them down. Off went the three of us on the Tube to the Leicester Square Odeon (half an hour distant on the Northern Line). I clutched my mother’s hand tight, always terrified of being swept off the platform by the draft of an approaching Underground train. Settled into my seat at the Odeon at last with a packet of toffee Poppets, I watched the inexplicable film. Why was nothing happening? This was so boring . . . no fights, no space rockets, no faithful animal jumping on the villain like Shadow the Sheepdog. It was just people talking! And then the climactic scene, a gigantic close-up of the two stars kissing. Who were they? Grace Kelly and Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief? Or Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift in A Place in the Sun, their beautiful faces contending for our attention?

What had shocked me was this. I understood that it was two actors on the screen, simulating fictional characters, but how could they possibly act something so intimate as a kiss? Could grown-ups pretend to have emotions? A whole world of potential deceit opened up before me. It was a disturbing discovery, like finding out that Father Christmas did not exist, or that my parents had sex. (And perhaps there was an unspoken fear, that they only pretended to love me!)

Ten years later, in a philosophy class at school, I discovered that Plato shared my confusion and concerns. In the ideal state he describes in The Republic, poets and actors are banished for giving a false representation of reality. By imitating actual people, they commit a crime by leading their audience away from the truth. This is a bizarre and reductionist view of theatre and the arts, of course, but I could understand the philosopher’s horror at people pretending to be other people and simulating emotions they do not have. It’s not so far from the horror we experience when watching a zombie movie, as familiar, homely characters become the Living Dead. This reaction also recalls the fascination of ‘did they or didn’t they?’ Decades after they appeared together in Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie still get asked whether the rumour is true that they actually had sex on camera during a bedroom scene. We continue to be intrigued, confused, and sometimes troubled by the phenomenon of people acting someone completely different.

Acting is a very strange profession. Our relationships, and society in general, rely on individuals behaving consistently and ‘in character’. To pretend to be someone else, or about how we feel, is to be suspicious, untrustworthy, and possibly criminal. In a theatre, however, we give an entire profession a licence to lie. Actors ‘shape-change’ into other people, in a way that would be terrifying in real life. They not only behave, dress, and move differently, they kiss people they hardly know, as though they were lovers. They lie in bed together naked and pretend to have passionate sex. It is as though they were possessed by demons.

Over a year, a single actor might need to behave convincingly as half a dozen different people. A Tudor princess. A NSW cop. Someone in an ad, overwhelmed with joy by a new breakfast cereal. It’s a curious job description, that makes actors very special people. Does the regular pretence of emotion and intimacy affect how actors relate to others? Of course not. But they are human too. In secret imaginings, we have all done things quite unlike our usual selves. We may all have dreamed of behaving in ways quite unacceptable in real life. To have such fantasies is entirely normal. ‘The virtuous man contents himself with dreaming that which the wicked man does in actual life,’ wrote Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams.

Transgression only occurs when private dreams leak across into ‘actual life,’ when other people are affected – for example, if the fantasy of a flirtatious relationship with a colleague slips into unwelcome touching and harassment. In dreams begin responsibilities: we might imagine something in our heads, but are culpable for acting on it in a way unwanted by another person. Recognising that distinction is an important part of growing up, and one that I was still too young to understand as those gigantic lips met above my head at the Leicester Square Odeon. For some people, however, it seems this distinction eludes them long after childhood.

Image: Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift in A Place in the Sun (1951).

“Over a year, a single actor might need to behave convincingly as half a dozen different people.” And weirdly, we always seemed quite prepared to believe in them as half a dozen different people. Our ability to suspend disbelief in the interests of the story seems amazingly powerful – though I have to say I’ve found that harder and harder in recent years as actors and actresses (delightful word, which I refuse to stop using) started to appear as versions of themselves in advertising for perfumes, watches, coffee, gambling and so on. The fourth wall is constantly breached and as a result I can no longer watch Hollywood productions with big name ‘movie stars’ because my disbelief will no longer be suspended…

Yes, it’s a weird phenomenon, the more you think of it. (Remember a child asking you to play-act a monster, but then getting scared and you have to stop and ressure them, ‘it’s only daddy’ or whatever.) And there are some actors who transcend over-exposure – Cate Blanchette, for example, can be almost unrecognisable by sheer force of acting.