‘[Pale Fire] unlocked my understanding of K.’

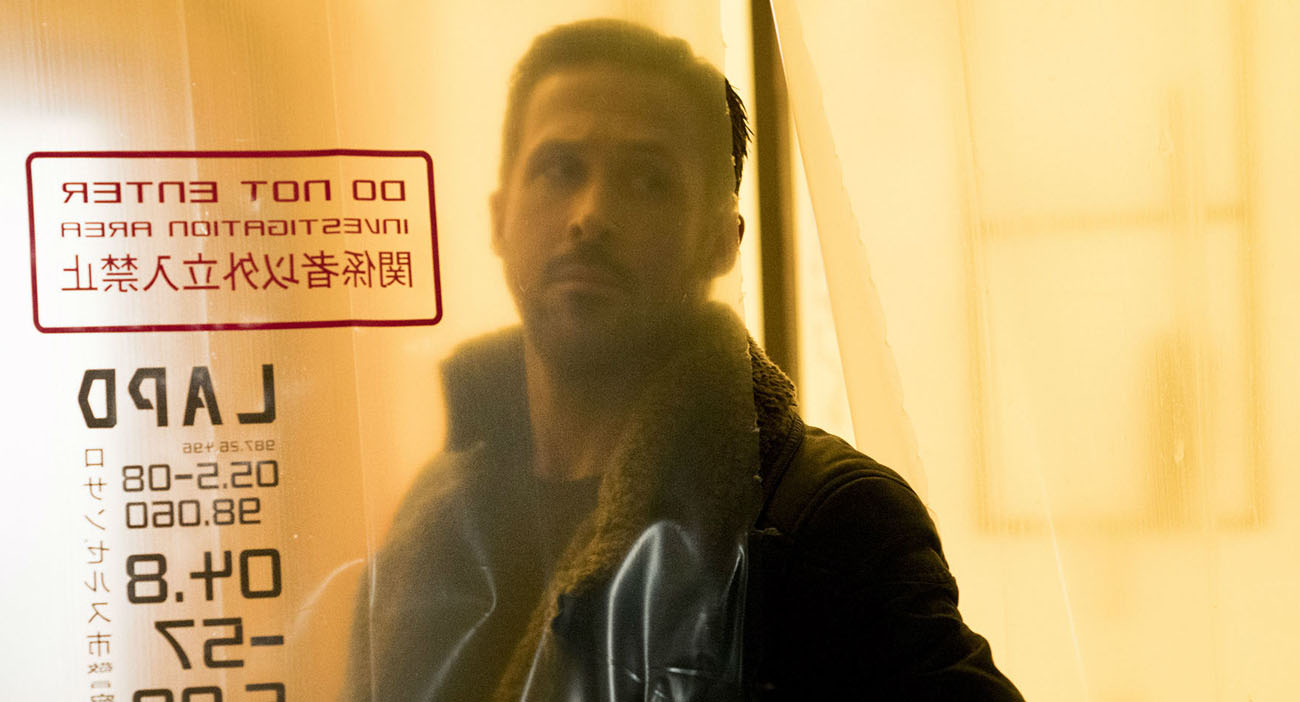

Ryan Gosling

Spoiler alert

Recent years have seen a succession of thoughtful movies about robots, artificial intelligence, and aliens: Her, Ex Machina, and Under the Skin, among others. As well as concerns about technology, these also explore current anxieties about society and what it means to be human. Also noticeable is the sympathy invited for non-human entities (a strategy cleverly exploited by the plot twist in Ex Machina). In this, they are faithful to the origin of almost all robot-themed stories for the last two centuries, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein:

‘I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine show signs of life and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion.’

It was not only Frankenstein’s monster which was ‘born’ in 1818, but one model of the Romantic hero: a misunderstood outsider, persecuted and hunted by society for being different. This archetype has lived on in books and movies, evolving to reflect our changing concerns and anxieties.

Blade Runner 2049 must have surprised even avid fans of director, Denis de Villeneuve, by its beauty and depth. The terrible and majestic visions it conjures (reminiscent of the paintings of John Martin) combine with a poignant attention to the emotional life of the characters. First among these is Agent K, a replicant employed by the LAPD to find and destroy any surviving Nexus-8 replicants, which had developed free will and revolted in the 2020s. Ryan Gosling’s muted characterisation perfectly conveys the replicant’s calm, ruthless efficiency at killing.

When all is said and done, Agent K is, after all, just a very smart toaster with good looks, who’s handy with a gun.

Gosling also hints, though, at the curiosity and emotional turmoil which well up inside K after discovering the mysterious ‘6.10.21’ inscription which sets the plot in train. As a Nexus-9 replicant, K is designed to be obedient and truthful; increasingly, though, he learns to lie and disobey, as though experience and memory inevitably lead to development of free will and imagination, despite his programming. Like the protagonist, K, in Kafka’s The Castle, Gosling’s character is alone and treated with disdain in an indifferent, broken world. LA in 2049 has little civil framework and seems dominated by a technology corporation expert in AI and contemptuous of the law (does that sound familiar?).

As the Shelleys and others recognised 200 hundred years ago, the new industrial capitalist economy would break down existing social relationships and drive people into isolation as individual workers and consumers. To recognise and revolt against this is to be condemned as an outsider: a Romantic tragic hero, like Frankenstein’s monster and all his children, like Agent K.

Blade Runner 2049 is not shy about acknowledging this literary and cultural context which contributes to its richness. The most prominent – insistent – presence in the movie, though, is Vladimir Nabokov’s brilliant, perplexing 1962 follow-up to Lolita: the novel Pale Fire. Lines from the work are twice used in a ‘Post-Trauma Baseline Test’ on K, and he has a copy of the novel at home. His virtual girlfriend, Joi, offers to read it to him, but he says, ‘no, you hate that book,’ showing that they have discussed it before.

Pale Fire has variously been called, ‘a Jack-in-the-box, a Faberge gem, a clockwork toy, a chess problem, an infernal machine, a trap to catch reviewers, a cat-and-mouse game, a do-it-yourself novel’ (New Republic), and ‘the great gay comic novel’ (Edmund White in the TLS). The novel purports to be the critical edition of a 999-line poem by John Shade, with a copious critical apparatus by his supposed friend, Charles Kinbote. The poem concerns Shade’s drowned daughter, time, and death, but Kinbote’s notes soon reveal him as a quite unreliable, mad fantasist, interpreting the entire poem as being about him and his secret life as the exiled king of a non-existent Ruritanian kingdom. It is perplexing, delightful, funny and moving all at the same time.

The parallels between Blade Runner 2049 and Pale Fire run deep, beyond the overt references, to enrich our understanding of the movie.

Worlds within worlds

In 2049, Agent K is an artificial being (with the same initial as Kinbote). As a replicant being, he seems defined by the corporation which created him. After discovering the mysterious inscription which matches a childhood memory, though, he begins to imagine himself within an alternative narrative: that he is actually the secret child of Deckard and Rachel. He then finds this is not true: that he was given the DNA and memories of their daughter, Ana, as a way of hiding her existence. By the end, we are left with the question of whether K was actually programmed to find Ana, not operating under free will after all?

In Pale Fire, a poem by John Shade, is published within a critical apparatus by scholar, Charles Kinbote. The reader knows these are actually both characters in a novel, each with their own conflicting fictional world. Kinbote’s mad reveries are actually no more ‘real,’ then, than Shade’s moving reflections on death and the imagination. A convincing case has been made that Shade is intended by the author to be the invention of Kinbote. An equally convincing case can be made that Shade playfully invented Kinbote, and is not even dead when the work is published. Nabokov himself stayed mum on the topic, just as the films’ makers cannot be drawn on whether Deckard is a replicant.

Pale Fire also has a little-known place in the history of computer science. The novel was well-known to Ted Nelson, renowned inventor of hypertext and one of the fathers of the World Wide Web. Working at Brown University in 1969, he recognised Pale Fire as a revolutionary literary metafiction and received permission from Nabokov’s publisher to create an electronic version, to demonstrate the possibilities of a hypertext document.

Agent K’s pale fire

‘The moon’s an arrant thief, And her pale fire she snatches from the sun,’ wrote Shakespeare in Timon of Athens – the source of Nabokov’s title. He uses this quotation to muse on whether memories and imagination can be as ‘true’ as actual events. In Blade Runner 2049, a major theme is whether a replicant with ‘memories,’ experience, emotions, and free will – a pale reflection of a human – can be as real as natural-born person. If so, we bear them the same responsibility as a god to its creations, as a parent to its children.

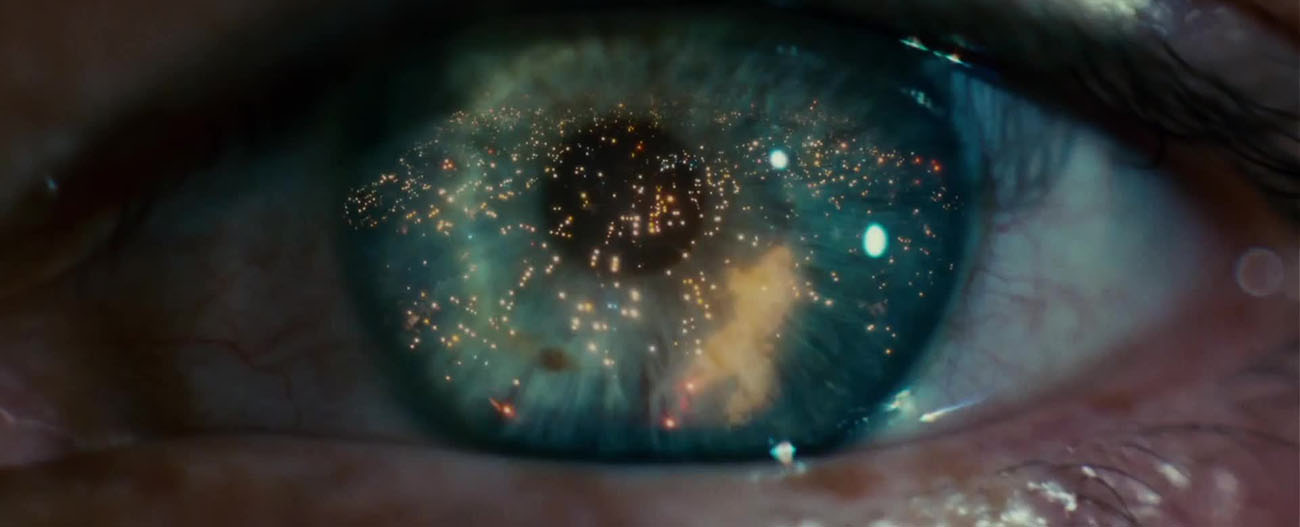

Eyes – the ‘windows of the soul’ to the ancient Romans – are a dominant motif in the Blade Runner movies. In both, examining the eye is a way of identifying a replicant. Eyes and sight are important in Pale Fire too. In the opening lines, we read:

All colors made me happy: even gray.

My eyes were such that literally they

Took photographs. Whenever I’d permit

Or, with a silent shiver, order it, Whatever in my field of vision dwelt –

An indoor scene, hickory leaves, the svelte Stilettos of a frozen stillicide –

Was printed on my eyelids’ nether side

Where it would tarry for an hour or two,

And while this lasted all I had to do

Was close my eyes to reproduce the leaves,

Or indoor scene, or trophies of the eaves.

There are 15 references to eyes in Pale Fire, principally as a way of recording memories or conjuring imagined or remembered scenes. Ridley Scott explains this in an interview: ‘The eye is really the most important organ in the human body. It’s like a two-way mirror; the eye doesn’t only see a lot, the eye gives away a lot.’

The secret letters

When K examines DNA records to search for Deckard and Rachel’s child, he finds two identical people: a dead female and a male. (This is a rare scene in the movie that doesn’t work: he identifies the matching records by supposedly scanning millions of GATC sequences with his bare eyes. It would also mean the two people would look identical, which K and Ana do not.) Nevertheless, this typographic discovery is a revelation to K: he realises that the child existed, is a male, and still alive. He discovers otherwise later, but this typographic sequence starts him on the trail that leads to Ana.

In Pale Fire, Shade recounts a vision he saw while having a heart attack:

A sun of rubber was convulsed and set:

And blood black nothingness began to spin

A system of cells interlinked within Cells interlinked within cells interlinked

Within one stem, And dreadfully distinct

Against the dark, tall white fountain played.

This is the exact wording chosen by the scriptwriters for K’s post-mission test on K in Blade Runner 2049. Coming across another person’s near-death experience which also mentions ‘a tall white fountain,’ Shade seizes this as evidence of an after-life, that his daughter may still exist after death. Soon, though, he discovers it was a cruel misprint – the word was ‘mountain’ not ‘fountain’.

This mistake was the point, Shade realises: that he is somehow being played with, stumbling through life in search of patterns. He has a revelation that he is part of ‘a game of worlds promoting pawns/ To ivory unicorns.’ In the original Blade Runner, of course, a much-discussed topic is the unicorn dreamed of by Deckard, and then seen as an origami figure left by his colleague, Gaff in the final scene, suggesting that Deckard may be replicant himself. In Blade Runner 2049, K’s DNA sequence of GATC similarly contains misleading typography which inspires, disappoints, and finally takes him nearer the truth.

Snow falling on replicants

Snow is a persistent motif in Blade Runner 2049. Joi, K’s AI companion, holds out her hand to catch snowflakes, but sees them pass through her hologram body. Later, Ana (Deckard’s daughter) creates a virtual mini snow-storm which falls just over her, saying, ‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ to her father. What neither of them know is that K is dying outside at that moment, lying supine while real snow falls on him. He has a faint smile on his lips, happy that he has given his own life to save Deckard and reunite him with his daughter – proving to himself that he is not just a machine but a living thing. At this moment, the ‘Tears in the rain’ music from the original Blade Runner plays. It inexorably reminds us of replicant Ray Batty’s dying words after saving Deckard’s life 30 years before: ‘I watched c-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.’

In Pale Fire, snow is also mentioned a total of five times, evoking ‘that crystal land’ of his imagination where all things might be possible, where his dead daughter might still be alive. As in the movie, Nabokov’s novel ends in a death which is accepted and valued as a necessary part of life; the poem is ‘completed’ by an absent 1000th line, missing because the poet has been shot at that moment.

Father and daughters

Despite the extraordinary visuals of Blade Runner 2049 and the literary pyrotechnics of Pale Fire, the emotional power of both movie and novel is drawn from their quiet heart: a father’s love and loss of a daughter.

After the death of Rachel in childbirth, Deckard lives in hiding with their daughter, Ana, first-born of a replicant. While she is still young, he gives her up and deliberately loses contact as a way of saving her life if he is ever hunted down. As far as Deckard knows, he will never see again the only person he loves – sacrificing his feelings for her sake. The climax of Blade Runner 2049 is their reunion, brought about by K, who has willingly sacrificed his own life for their sake.

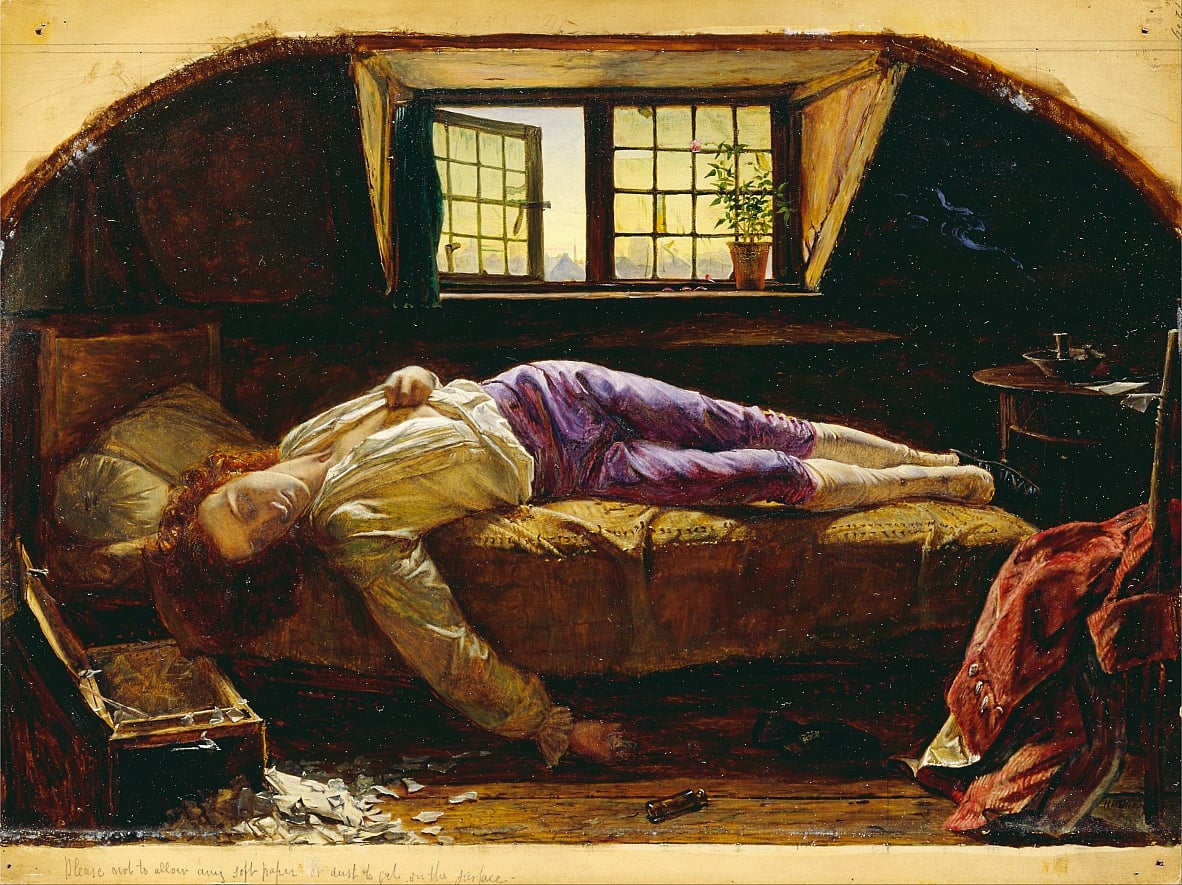

In Pale Fire, John Shade has lost his daughter – awkward, unhappy Hazel – to suicide or an accident. He is riven by grief, yearning to be reunited with her. The entire poem is a meditation on how this might happen, dabbling and rejecting absurd spiritualism, and finally realising that, while accepting her death, they can be together through the power of memory, imagination, and art which transcend time.

For Deckard, Ana, and Agent K – and for us as the audience – this is as good as it gets, and that is good enough. As John Shade writes:

But all at once it dawned on me that this

Was the real point, the contrapuntal theme;

Just this: not text, but texture; not the dream

But topsy-turvical coincidence,

Not flimsy nonsense, but a web of sense.Yes! It sufficed that I in life could find

Some kind of link and bobolink, some kind

Of correlated pattern in the game,

Plexed artistry, and something of the same

Pleasure in it as they who played it found.

Great blog. I’ve never read Pale Fire, but will now seek it out. And one day I will watch Blade Runner all the way through. I’ve seen the first hour many times…

Thanks, Bob. 2049 is extraordinary, I’ve seen it twice at Imax. Squalor and beauty, cruelty and love . . . just like real life really, only moreso.

Excellent piece, Paul. Fascinating.

In Pale Fire, the cruel misprint changes nothing: the image of the tall white fountain had meaning not because it had some objective significance, not because it was empirical proof of an afterlife, but because Shade ascribed meaning to it.

Consequently, like John Shade discovering that his near-death vision was not shared, K realizes that his memory of a wooden horse didn’t belong to him after all. It means he is not Rachael’s child, that he’s not a miracle, not special after all, but it no longer matters. The moment K thinks he is more and wants to be more, he becomes more. His perception is reality. It reprograms him.

Yes!

I read Pale Fire in high school and didn’t understand any of it all. Years later I watched BR49 and thought it was one of the best movies I’ve ever seen but was curious as to the Pale Fire mentions. I watched the original BR after that then re-read Pale Fire. I started making so real surface life comparisons between the two and thought it was very cool

(I got autocorrected. some* level* not life) – contd. I’ve dove deep into the connections between the book and the movie and now that I understand the book it makes both all the more better. Thanks for your work.